It takes a certain breed of a human being to explore narrow, muddy and dark caves. And enjoy it! I have been pleasantly surprised by exploring some bat infested caves in mainland Malaysia, but it wasn´t that deep and one could move around relatively easy. At one stage stand up. And I knew the way in and out. It was fascinating! But like Jut head into the unknown world of un-explored caves, for me that is bigger than jumping from the limit of the sky. What if you got stuck! And after reading this interview with Jut below, I find him very inspiring and should be read by everyone of all ages who needs to get the extra little push to choose a more interesting life. Thank God Jut you choose the world of caves instead of becoming an investment banker!

Caving; Get Involved With Jut Wynne

An

Interview

1. What were you like as a kid? Please tell me about your early years.

Since I was a child, I had the heart of an explorer. During the summers and weekends of my adolescence, I would leave home early in the morning to explore the woods, ditches and marshes throughout my south Georgia island home. Oftentimes I would not return until long after sunset – much to the chagrin of my parents. While on my “expeditions,” I studied the land and I learned how to read animal signs and determine where certain animals were likely to be found. As a result, I brought home a menagerie of wildlife including snakes, frogs, turtles, baby raccoons, and birds. Once, a marsh hen, disoriented after a high windstorm, made a miraculous recovery after I brought it home. It crashed into furniture and broke a lamp among many other things. My mother yelled at me as I captured that poor bird and took it outside. My thirst for understanding the natural world and the animals that reside within it ultimately led me into research.

2. Please tell me about your education.

I’ve spent more time in school than out of school. Given this, I should be a whole-heck-of-a-lot smarter than I am. After finishing 12 years of primary and secondary school I spent the first few years of my college education deluded in thinking I was going to become a wealthy investment banker. Three years later, I finished my undergraduate degree with a major in Communications and minor in Anthropology from Georgia Southern University. This education “qualified” me to become a “shovel bum” field archaeologist. My interests ultimately shifted to environmental science and I applied for, and was awarded, a fellowship to study Human Ecology through the UNESCO/ Cousteau School of Ecotechnie at the Free University of Brussels in Belgium. I earned a post-graduate certificate for my studies there and then, realizing I could no longer tolerate a big congested European city, I moved to Flagstaff to pursue a M.S. degree. I completed my Masters in Environmental Science and Policy at Northern Arizona University in 2003, where I focused on modeling migratory songbird habitat using GIS and remote sensing. Two years later, I began a PhD program in Biological Sciences. I will be completing my PhD in May 2013, and currently all of efforts are concentrated towards reaching the finish line.

3. How and where did your interest in caving start?

My interest in caving evolved through my fascination with bats and my desire to study bat habitat ecology. This interest, coupled with my inability to turn down fascinating projects, resulted in me leading a cave bat study in Belize. I was approached by a colleague with the Belize Ministry of Archaeology who was studying the archaeology of Actun Chapat Cave. This cave was rumored to support a quarter of a million bats.

An ecological inventory had yet to be conducted and there were plans to open this cave to eco-tourism so I conducted an inventory in 2001. You can see why I couldn’t decline the opportunity.

During this study, I was completely struck by the beauty of the subterranean world. The jet black darkness, the amplification of the sound of every water drop crashing upon the cave floor, the flutter of bat wings at they flew by my head, the acrid smell of guano, and the amazingly bizarre animals that call the subterranean world home. It was on this trip that I realized I was going to become a cave scientist. The Journal of Cave and Karst Science published the results of this work in 2005.

4. Now that you’ve been caving for a while what is it about caving that made it your passion?

Science, endorphins and adrenalin, of course! I’m passionate about the study of caves and understanding why animals select to live where they live. I’m also fascinated by evolution and how, over time, animals become adapted to living in a particular environment. Caves provide me with the opportunity to investigate these and many other interesting scientific questions. There’s also the endorphins and adrenalin factor. Any caver knows that working underground can be exciting. I’m always stoked to enter the subterranean world. You never know what you’ll encounter and what you’ll learn from any underground experience.

5. Cavers cave for a variety of reasons and for you caving goes beyond recreation. What’s your motivation?

I am motivated by a desire to understand the subterranean world and share my knowledge with anyone who will let me talk about caves. I want to know how animals live underground, why some are more successful than others, and understand those habits that make both successful organisms and unsuccessful organisms. For the past several years I’ve also been driven by a desire to develop techniques for identifying cave targets on Mars for robotic exploration. Public outreach and education is very rewarding to me. Over the years, I’ve Sharing knowledge that acquired with hundreds of folks including students and the general public throughout the U.S., Chile, Hawaii, and Easter Island.

6. You’ve done quite a bit of globetrotting over the years. Where have you traveled and where have you been caving?

Beyond cave research, I have conducted numerous projects in the fields of archaeology, ecology, paleontology, and planetary sciences. I have worked in some of the most remote areas in the southwestern United States as well as in Belgium, Belize, Bolivia, Chile, Easter Island, Scotland, Mexico and Hawaii. To date, I’ve studied caves throughout the southwestern U.S., Belize, northern Chile, Easter Island and Hawaii. However, India and New Guinea are on the radar. I’m currently collaborating with the Malnad Wildlife Group in Shimoga, Karnataka, India on a project. We have one proposal in review and hopefully we’ll be able to start work there next year. As for New Guinea, it’s been a dream of mine for a while and I’ve recently made some connections that may help may this a reality. Time will tell, of course…

7. Arizona and the desert Southwest seem to be your local stompin’ grounds. Please tell me about your Grand Canyon work that includes LIDAR mapping and deploying instruments.

The work on the north rim of the Grand Canyon is part of a bat hibernacula habitat characterization project. We identified the largest known bat hibernacula in northern Arizona in February 2010. As part of a pilot project to understand microclimate and habitat requirements of hibernating bats, we’ve deployed over 40 temperature and relative humidity instruments deployed along the length of one cave hibernacula. We’ve been collecting hourly temperature data at both sites for over a year. Also, using a combination of 3D mapping techniques and LIDAR technology, we’re developing high-resolution 3D maps. Our objective will be to take the plotted location data of all instruments and then use this information to develop 3D interpolative models of temperature and relative humidity. We’ll then take the 3D locations of hibernating bats that we collected in February 2011 to better identify microclimate conditions for hibernating bats and potentially make predictions regarding other suitable hibernations sites within the hibernacula cave. This information will be useful in understanding why bats hibernate in certain parts of a cave and not others. Also, by collecting temperature and relative humidity data of these two caves, we will be able to quantify the microclimatic conditions of these two bat hibernacula.

8. Also you’ve made numerous discoveries in relationship to your bat and insect research, what are you finding?

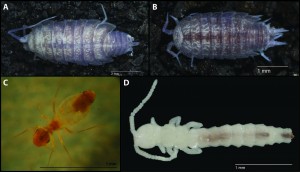

We have documented numerous interesting aspects of natural history of northern Arizona caves over the years. We’ve documented five bat maternity roosts and three cave bat hibernacula. And when it comes to spiders and insects, colleagues and I have identified three new genera and around 30 new species from southwestern U.S. caves. Of these, we have at least six cave-adapted arthropods. Additionally, we’ve identified at least six new species of insects from Rapa Nui (Easter Island) caves as well. While these discoveries do contribute to the overall knowledge base of natural history of both the southwestern United States and Rapa Nui, my objectives are not to merely catalog the presence of roosting bats and identifying new arthropod species. That is not why I study caves. Science advances in baby steps and first we must document what occurs within these caves. With more knowledge, we can then begin to formulate hypotheses to help understand how and why the organisms use caves and “make a living” as well as make recommendations to best manage these resources. To me, the latter is where the “rubber meets the road” in cave science. And, that’s where I aspire to make my contributions.

9. Please tell me about your NASA supported cave projects.

I have been fortunate enough to work on three different projects supported by the NASA Exobiology Program. In 2005, NASA funded a proof of concept study where we cut our teeth on how to monitor and collect data of cave microhabitats and how to plan aircraft missions using thermal imaging systems. For the past three years, I have been managing a project to develop techniques to detect caves on Earth and identify candidate cave sites on Mars for further imaging. The lessons learned from earth-bound applications will be used for detecting caves on Mars. Several years ago, Glen Cushing identified several large deep pits on the northern flank of Arsia Mons on Mars. This prompted us to look for terrestrial analogs, and this resulted in a third funded project to study pit craters on the Big Island of Hawaii. I am a co-investigator on this project. Our objective is to collect temperature data and then model the thermal behavior of pit craters with and without caves to see if we can tell the difference between the two. This knowledge will be informative in predicting whether we can tell the difference between a pit craters with a cave and one without on Mars.

10. The Atacama and Mojave Deserts may be good places to help NASA understand how to detect caves on Earth and Mars. Please tell me about your Earth-Mars Cave Detection Project.

I have been blessed with the opportunity to work with an incredibly talented team of physicists, planetary scientists and engineers on this project over the past several years. Since 2005, we have been improving our ability to detect caves using thermal and visible imaging and correlating the temperature signatures in these images to ground-based temperature measurements.

We have been refining these detection techniques in the Atacama Desert, northern Chile and the Mojave Desert, southern California. Our objectives of this project are to: (1) identify times when differences between cave entrances and surface control stations are optimal and thus detection in the thermal infrared is optimal; (2) compare the thermal behavior of caves to non-cave features (e.g., shallow alcoves), and; (3) develop simulation models of the thermal dynamics of Martian caves and surface. Through these efforts, we hope the results of this project will aid us and perhaps others in developing a systematic approach for selecting candidate sites on Mars for exploration. Once done, I’m hopeful NASA will send in a rover into some of these Martian cave sites to look for evidence of life.

11. How did you collaborate with NASA with your high tech aerial data acquisition on the Mohave project?

The acquisition of aircraft-borne thermal imagery was part of the three-year project that I mentioned earlier. We worked with NASA-Dryden Flight Research Center for one reason – they’re the best in the business. NASA-Dryden has a long history in aircraft flight research and we knew they would be able to provide us with the level of expertise necessary to get the job done. We used the Quantum Well Infrared Photodetector (QWIP) developed by Dr. Murzy Jhabvala at NASA-Goddard to collect the thermal imagery. Murzy is a co-investigator on the three cave detection projects that I’m involved with and has been a major contributor to developing techniques for detecting caves. We flew a similar mission back in 2006 to collect thermal and LIDAR imagery from caves in Arizona and New Mexico. The 2006 mission was a great learning experience for both of us. This aided us in planning and executing a successful mission in the Mohave Desert. Murzy and I are currently working together to process more than 7000 thermal images that we collected in April 2011.

I heard that the Discovery Channel rolled their cameras and followed your research in the Mohave Desert. And how did you come to appear on NASA TV’s This Week @NASA?

Discovery Channel and NASA TV were both interested in our work. Discovery Channel has been interested in the work over the years, but for one reason or another, they weren’t able to join us in the field until recently. They wanted to cover both the fieldwork associated with pulling our temperature and barometric pressure instruments and the aircraft mission to collect aircraft-borne thermal imagery. Discovery Channel coordinated with NASA-Dryden Public Affairs to collect B-roll of us at Edwards Air Force Base as well as in the aircraft. Then, Discovery shadowed us in the Mojave for a couple of days. Dryden produced a story that was recently featured on NASA TV’s This Week @ NASA.

12. Most visitors to Easter Island, aka the Polynesian island of Rapa Nui, are there to see the spectacular moai (the giant anthropomorphic statues) and for its tumultuous cultural and ecological history. And you went underground, why?

For science! While we cannot negate the manner in which the ancient Rapanui people changed the internal structure of many caves, my research interests extend beyond the human component.

I am studying both the surface and cave-dwelling arthropod communities on Rapa Nui as part of my dissertation research. We know the surface environment was battered by a successful and complex society that placed extreme pressure on an already fragile ecosystem. The English and later Chilean Navy stocked the Island with goats and the goats were a tremendous nail in the ecological coffin.

I have formulated many questions during my past four trips to the “Navel of the World.” First, I believe cave-adapted arthropods exist on Rapa Nui despite extensive surface disturbance. I’ve also learned that because cave communities are characterized primarily by non-native arthropods, the composition of species will differ when we compare between caves. I suggest cave communities (characterized be mostly non-native species) will be trophically similar to a cave communities populated by mostly native species. Finally, cave communities on Rapa Nui will contain fewer species when compared to ecosystems where surface disturbance and non-native species introductions are low. I hope to compare data from some Hawaii caves to help address these last two questions.

I have been working with Corporacion National Forestal de Chile (CONAF) and Consejo de Monumentos on cave resource management issues on Rapa Nui for the past four years. I am hopeful that my fieldwork in January 2014 will provide more opportunities to make science-based management recommendations that will be implemented into the park management plan for Rapa Nui National Park.

13. Academic and professional rewards that come from discovering a new species are understandable. You’ve been involved with discovering dozens of new species and three new genera. What does it feel like to lay eyes on a critter and share its existence with the world?

The subterranean world is one of the last frontiers of scientific exploration on this planet. So, it is of little surprise that when we investigate a cave or cave-bearing region that has not been studied we make new discoveries. Nonetheless, when you peer down upon a cave-adapted animal in an unstudied cave, you know you’re likely looking at a new discovery.

But this can be a long road to hoe. Once we collect this presumed new species we then have to take it back to the bug museum, peer at it under a microscope, take copious notes, and then place a nice, museum quality label on it. We then send it to a specialist for identification (provided a specialist still exists). From there, depending on how busy this researcher is, we hear back from him/ her in three to six months. So, while discovering new organisms is truly exciting, the science to confirm its novelty is often tantamount to watching the grass grow. However, once I have confirmation that we’ve discovered a critter new to science, I realize we are furthering our understanding of that region’s natural history.

The humble contributions I am able to make in my short lifetime are what I find truly rewarding. Perhaps more importantly, as a conservation biologist, my interests lie in taking the scientific information that we gather from caves and then making recommendations for management commensurate with the sensitivity of the resources encountered. To date, I have made recommendations for the protection of several caves that contain sensitive biological resources. Some of these caves are now protected.

14. So, you’re now focusing all your efforts to completing your PhD. Please tell me about your dissertation.

My dissertation is focused on understanding and modeling diversity and distributional patterns of cave-dwelling arthropods in the American Southwest and Pacific Islands. I am investigating several aspects of cave community ecology including community composition and structure and identifying the habitat parameters driving diverse cave ecosystems. I am: (1) developing and testing inventory and monitoring protocols for studying cavernicolous arthropod diversity; (2) characterizing the community structure and developing a functional classification system of cave-dwelling arthropods; and, (3) using and examining readily available landscape variables and select cave microclimate and habitat variables to develop spatial models to predict cavernicolous arthropod diversity.

15. You’ve been honored in a variety of ways.

Yes, I have. Last year, Northern Arizona University presented me with the “2011 Most Promising Graduate Student Researcher” award, and about two months ago, a cave‐dwelling Tenebrionid beetle has my namesake, Eleodes (Caverneleodes) wynnei. Also, I’m a Fellow in both the Explorers Club and Royal Geographic Society. I currently serve as Chairman of the Southwest Chapter of the Explorers Club and serve on the Science Advisory Board of the Easter Island Foundation. But perhaps the biggest honor was when I was a featured scientist in a 4th grade science text in Spain. I was listed as “Dr. J. Judge Wynne.” So, not only did they confer an honorary doctorate upon me, but they also made me a judge! What a day!

16. Besides caving, exploration, and scientific research what are some of your other interests?

I’m also an endurance athlete and yogi. I train regularly as an endurance runner, cyclist, mountain biker, and in numerous winter sports. I have competed in over 30 races since 2005 that include running and multi-sport events across the southwest. Among my favorite races are the Imogene Pass Run in Colorado and the Mt. Taylor Winter Quadrathlon in New Mexico. I will be competing my forth Imogene race this September and my third Mt. Taylor race in February.

17. Let’s say a young person asks you for information and advice about getting started in caving. What would you tell her or him?

Over the years, I’ve spoken with hundreds of kids about caves and cave exploration. I am always truthful in emphasizing the potential risks associated with cave exploration and at the same time I emphasize the potential impacts associated with the recreational use of caves.

What I emphasize most are “Leave No Trace” ethics and being properly prepared to explore caves. Regarding Leave No Trace, I stress the fragility of cave ecosystems and the sensitivities of bats to human disturbance. I instruct students to leave a cave at once if they encounter roosting bats. As for preparations, I explain what I have had done and learned to be as safe as possible when working underground. I describe this as “preparing for battle.” I tell them about my experience, my technical and medical training, and I tell them what equipment I bring into a cave – 3 sources of light, extra batteries, plenty of food and water, first aid kit, extra clothes, etc.

18. Many young people shy away from studying science curricula. How do you encourage girls and boys to pursue studies in science?

I have worked actively in education outreach since 2003 and when in the classroom my objective is simple – I want to make science fun. If it’s fun and entertaining students are likely to retrain the information. I often enter the classroom in full technical caving attire. Student’s faces light up and they immediately start asking questions about my gear. At that point, I know I have their attention! I’m also a firm believer in props and multimedia. I always bring bug and bat specimens into the classroom and show videos of caves and cave animals. The kids eat it up. I’ve always said that if I can get just one student hooked on science, then I’ve done my job.

One of the most important things I emphasize is that science is “cool.” Scientists are sometimes viewed as nerdy or un-cool, the antithesis of the varsity high school quarterback. I often use the “astronaut example.” Going into space easily has a cool factor of 10, and kids love astronauts. Many astronauts have advanced degrees and these are often, if not always, rooted heavily in math and sciences. So, I tell them this, and at the same time I encourage students to study hard and pursue math and science courses vigorously.

While I can’t say that my work is in any way comparable to that of an astronaut caves are in fact mysterious environments. In some ways, I guess, caves are like outer space. Many of the students I speak with may never venture into a cave in their entire life — just like most will never travel outside the earth’s atmosphere. So, when I speak with students about cave research it’s not difficult to hold their attention. I reckon I’m blessed with an intriguing topic of study!

19. What are your foremost concerns with terrestrial caves and their ecosystems today?

Climate change is perhaps the greatest threat to caves today, secondly, White-Nose Syndrome. Climate change is considered the greatest threat to the biodiversity of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. Currently, a growing body of work exists to understand and predict the effects of climate change to these ecosystems and the flora and fauna that call these systems home. However, there is vanishingly little being done to understand how climate change may affect cave ecosystems and troglomorphic organisms. While caves are somewhat buffered environments, I do not expect them to be impervious to global climate change. Research that Dr. Tim Titus (USGS-Astrogeology, Flagstaff) and I have conducted suggests that changing cave temperatures are likely to experience a lag effect. By extension, the impacts to troglomorphic taxa and bats will be delayed, but I suspect organisms will ultimately be affected in ways similar to their surface-dwelling relatives.

This being said, caves are living laboratories that harbor some of the most unique animals on the planet. We still know very little regarding most of these animals’ life history characteristics and thus we really don’t have a good reference point for monitoring most cave-adapted species. One could argue that we’re racing against a clock. We know little about most cave ecosystems but we need to know about these systems to establish protocols to monitor these systems under a climate change paradigm. The race is on to understand these systems. I am hopeful that our work on cave microhabitats and cave climate change will provide some of the information necessary to at least begin to ask the right questions so that we can best monitor cave microclimates and ecosystems.

Regarding WNS and Gd – at the moment, the “fungus among us” has us beat. Dr. Jeff Foster and colleagues at MGGen, NAU, are working on an assay to specifically identify G. destructans from all the other Geomyces species present in the environment. While this undoubtedly will be a important step, we still have a lot of work to do. We still lack the preventative and curative tools. While we may ultimately be able to identify GD, we still don’t have a means to prevent this fungus from killing bats.

For example, in Arizona, we have little information on cave hibernacula locations and know little about the habitat requirements of cave bat hibernacula. Our research on North Rim Grand Canyon will only partially address these questions. In the western U.S. we first need to learn where the bats are hibernating and then develop monitoring protocols to both monitor habitat and potentially detect WNS early in these caves.

I am hopeful that the westward advance of WNS will spur land and natural resource managers to launch larger efforts to identify and monitor cave hibernacula, collect and analyze data on habitat requirements, and establish baseline soil microbial community information from cave hibernacula. Hopefully, these efforts will contribute to the information-base of hibernacula and Geomyces, and ultimately provide us with the information necessary to protect and conserve our declining North American bat populations.

20. How can interested cavers find out more about what you’re doing?

My website and blog site are easy to access. www.jutwynne.com and http://jjudsonwynne.blogspot.com

Jut Wynne is a PHD-student, explorer, Fellow of The Royal Geographical Society and The Explorers Club. He has had one cave dwelling beetle named in his honor, Eleodes (Caverneleodes) wynnei.