It seems like yesterday, but it’s been more than a decade since I first visited Germany – an American baby-boomer with wide-eyed notions of WWII, particularly its aftermath and the Berlin Wall. The infamous landmark was something I had always wanted to see, so I made it part of my itinerary.

Built by the now-defunct German Democratic Republic in the early 1960s, the Wall separated East Berlin, occupied by the former Soviet Union, from West Berlin via a split negotiated after the War by the superpowers. Despite the 96-mile-long concrete obstacle, an estimated 5,000 people from the East still managed to escape to freedom in the West from 1961 to 1989, but another 100-plus lost their lives trying, many shot by East German border guards.

As communism collapsed, most of the Wall was dismantled. But a few parts still stand today, the most famous being the 4,320-foot-long East Side Gallery with more than 100 colorful paintings.

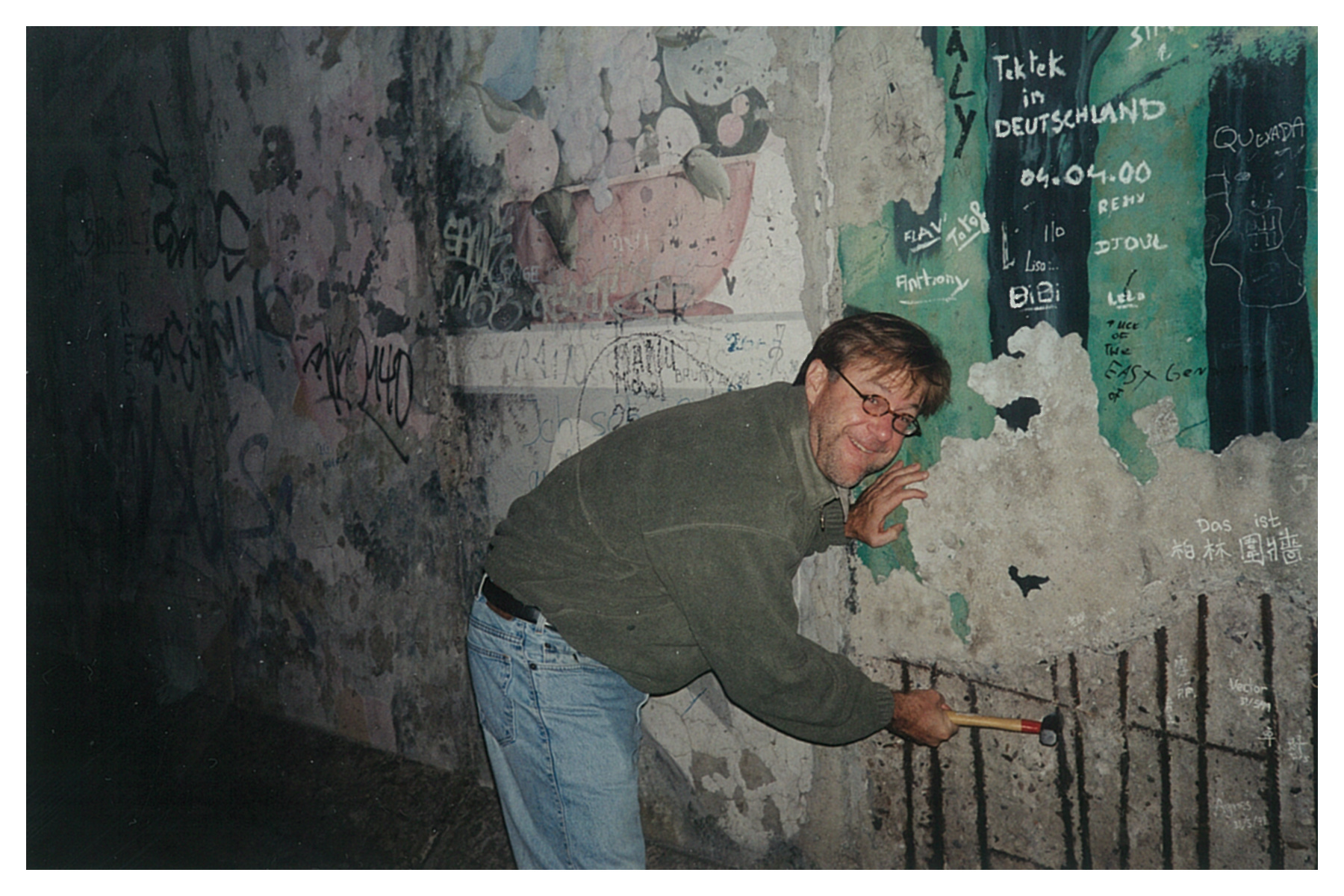

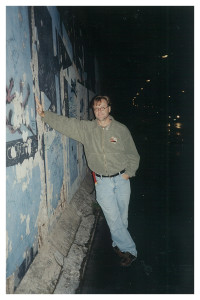

My target was the less obvious. On a chilly fall night, my friend and I headed over to A smaller Potsdamer Platz section. It wasn’t for drama that we traveled under cover of the dark. There’s an unwritten rule that tourists are not to take pieces off the remaining Wall, for obvious reasons. But I had always wanted a souvenir, and this seemed like the surest way to get one.

Armed with hammer and screwdriver, and dressed in nondescript clothes, I felt a bit like a cat burglar; I was nervous but also excited. My German friend, Rita, was more amused than anything else — why with this crazy American wanting a piece of the Wall! — and she humored me as we strolled along.

When we finally crossed a bridge approaching the Wall itself, my pulse quickened. I remembered watching in disbelief when TV network news showed protesters tearing the thing down in 1989, an iconic image seared into my brain like Neil Armstrong walking on the moon or Jesse Owens winning gold in the 100 meters at the Berlin Olympics.

After a check for passersby, I quickly removed the tools from my jacket pocket, set the screwdriver firmly on a protruding section of grey, graffiti-strewn concrete and smacked it with the hammer. Nothing happened. I hit the driver harder, and a little piece fell off. I gathered it up in a pouch, along with some dust that had also crumbled off. I smacked the Wall again, and another piece fell into my bag.

The rush I felt was unexpected. It was as if the entire Cold War, bottled up inside me since age six, spilled out: Sputnik and the space race, the Cuban missile crisis, the duck-and-cover drills we practiced in elementary school in case there was nuclear war, Soviet tanks on the Czech Republic’s bridge.

My friend, intrigued by my reaction, then took her turn. Like me, at first she had trouble trying to stay quiet and still hit with enough force to dislodge something. After a few tries, she got a chunk. We took some photos.

Sirens wailed in the distance just before we left, probably for a car accident somewhere in the city. But with my Cold War paranoia still intact, I was convinced the commotion was for us, and that we had better hi-tail it out of there. Rita chuckled, a big belly laugh really, saying the last thing the German police wanted was to bother an American over a piece of cement. They had better things to do.

Later, I shook some of the Wall dust from the bag, taped it to a postcard and shipped it off to my parents for a souvenir. Rita, who originally thought my idea was dumb, now said she was happy to have her own piece of the Wall.

A few days later we visited Checkpoint Charlie, with its famous museum of memories and relics from bygone days. It was fascinating and, to my surprise, hunks of the Wall were on sale there for between a few hundred and a few thousand dollars. Some were really impressive, with old metal rebar wire protruding from the concrete, like tentacles. Though tempted, I didn’t buy any (who knew if they were real?).

Safely back at my hostel were the smaller pieces – ones I had chipped off – and those were good enough for me. I had left my own mark, however insignificant, by lessening the mass of the Wall a smidgen, and maybe just a smidgen late.

Jim Clash is an Explorers Club Fellow and director, is author of “Forbes to the Limits” (Wiley, 2003) and “The Right Stuff: Interviews with Icons of the 1960s” (AskMen, 2012). He lives in New York.

Photos of Jim taken by Rita Schutt.