Natasha has lived in Dolinka most of her life. It is a typical post-Soviet village which could have been anywhere in Siberia. Pot holed dirt roads mixed with patches of paved road, one story houses, wooden fences, a feeling of everything quite run down, but full of strong and tough people, a few administrative buildings, a gas station, a few small dukas (shops) sellling everything from meat to valenkis (felt boots), a few people huddling around the village, old side by side motorcycles from the Soviet era, barking dogs, the smell of coal, many rusty Volgas and OASes, the odd new Landcruiser and on and off signs of the past. Often in the shape of leftover barbed wire, ramschacked buildings and the odd sign made up of the hammer and sickle. I have always been fascinated by these villages, most of all because I have come across some of the nicest, most generous and hospitable people I ever met. Dolinka was not an exception to the rule, in any way. It was built from the ground by the prisoners of KARLAG.

This is the actual place where the administrative building for KARLAG was located. Today the building has been turned into a museum called, Museum of Memory Of The Victims Of Repression, and it is one of few museums left on earth today, showing the evil side of Stalin´s penalty camps called GULAG. And it used to be center of all activity in Dolinka and still is to a certain degree, because the museum employs many local people. During our pre-research one of our big hopes was that we hopefully would be able to find somebody who had been on the other side. By which I mean, at least one of the guards or people employed by the previous Soviet government or someone who had actually been part of the GULAG administration, but we were almost sure this could be hard to realize. We went to Dolinka almost as quick as we arrived to Karaganda, just to see the museum and we started to ask around, and we almost immediately heard this story about a previous guard who had agreed to be interviewed by a big Russian newspaper and he had been turned into a monster and had died in a heart attack from having read the story about him. And those who told us that story, everyone single one of them said the guard was a good guy. But we got the feeling that finding anyone who would meet us, if there were survivors from the other side, would be hard. And we didn´t want to do as Claude Lanzemann in his epic film Shoah about the Holocoast hiding cameras and microphones. I am not saying it is wrong, but not our style. And, it turns out, it kind of sorted itself out, because we needed a place to stay and we got invited to Natasha. Her father had been part of the KARLAG administration.

We stayed with Natasha a couple of nights, she cooked the most amazing food for us and she, of course, had an extra ordinary story of life to share. A much younger man, Tolka, who was also employed on and off by the museum and also had a dramtic story of life, rented a small room of Natasha. Another really nice human being.

“So … me … so, I will start with the story of my birth” she starts sitting on a sofa: “I was born here, I don’t know who my parents were. I was found in the old cemetery here in Dolinka..24th June 1958. My father was a ambulance driver…He was going along a road and suddenly a calf jumped out with a bundle clutched in its teeth. And he could hear the sound of a baby’s cry. And he found me. He and mum didn’t have children. So they adopted me and brought me up. After some time, mum divorced Dad, she remarried, a chap called Nikolaya Ivanovich Popov, he was a military man. After the war… he was in the Great Patriotic War…he worked in Karlag as an ‘operative’. So…life went on…I have one son, he’s 32 … I have 2 grand daughters. I live here … what else can I say?”

Even though the interview hardly had started we all felt a bit tense here. Not because of her new stepdad being part of the KARLAg administration, but because we heard another story of survival.

“I’ve been working in the museum for 6 years. Prior to that I worked as a chief accountant for the police, for internal affairs. The story of my life is quite short. I was out of work for 7 years. My husband was alive then. He died in 2003. Then I was alone. I lived with my son, and then he left and now me and Tolik are here! In December he came to live with me and so that’s it! I live my life in Dolinka! We live a simple life, we don’t have anything special and we’re simple people. “

“What does your son do? Does he live here?”

“No, he lives in the Akmolensk area …He’s got his family … 2 daughters … he works as a driver. This is my house, it used to be owned by the state. It was built in 1924 by the first industrialists. There used to be a mill here. There used to be a big river behind my house. We moved here when I was six. When we used to dig up the potatoes in the garden, we used to find old millstones and use them around for flowerbeds! We broke them up, used them for flowerbeds….A miller used to live here. They made flour here. We found this out when we found some old documents, it became clear that this used to be a mill and the first industrialist lived here.”

“Did you talk about KARLAG?”

“We didn’t really discuss Karlag at home … it wasn´t really something we talked about. It’s only now people are talking about Karlag. Back then it was all under a shroud of secrecy. It just wasn’t openly discussed. I didn’t know much at all about it then and I have only started finding out things since I started working there.”

” So it wasn´t even mentioned by your stepdad?”

“Only hearsay … Dad didn’t chat about it at all. To be honest I never had any thoughts about it until all these awful things came to light, looking at the literature, when we started these guided tours. Alexandr Sergeyevich did these really well, Ksusha… then we started finding out a lot – Have you been around the museum? Have you seen the barrels? It’s a nightmare, its horrible when they explain that in the winter they couldn’t transport the dead, so they stored the bodies in barrels and salted them like mackerel. Just imagine … nightmare!”

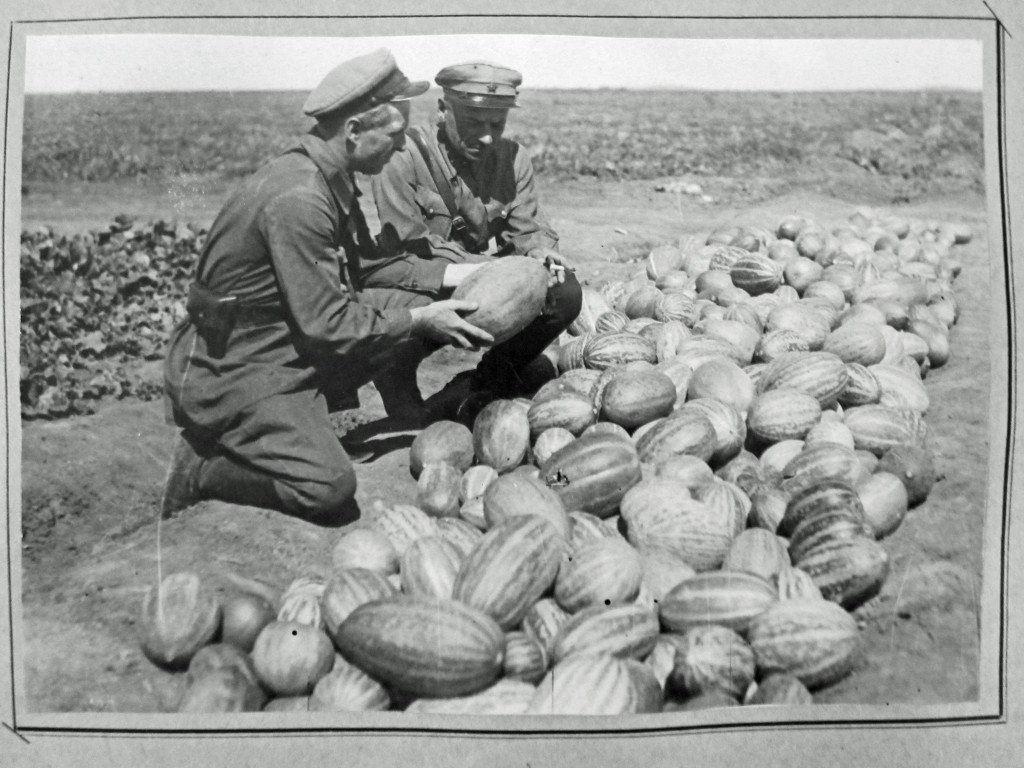

“People lived in very difficult times then. However, the forests and fields have gone … I remember when I was younger … they had fields full of potatoes …. Strawberries … flowers … we planted potatoes, carrots, flowers. All the irrigation channels were built by the prisoners from Karlag. The whole village, all the buildings were constructed by their own hands. It used to be so beautiful. Now it isn’t quite as pretty, the green is gone, the trees have been chopped down. This used to be quite a beautiful village. It’s a shame, I used to have photos of my dad in that building, but before anyone had even thought of having a museum here in Dolinka someone came from Alma Aty museum and I gave them so much stuff – my Dad’s medals, so many photos, yes? Had I known we would have a museum here I would of course have kept all of it and given it to the museum here. So, everything was given away then you can’t get it back! Of course, it was horrific, very scary times to live in. That’s the lot! That was the situation. God forbid this ever happen again.”

“Was life hard for your father?”

“Oh, no, he was a very resilient, very hard working, never complained. Alll his life, as I recall as soon as he and mum got married, and obviously when mum was in hospital I used to go to work with him. I was left in a visitors room, I wasn’t allowed to just run around the camp with him, yes? And so I don’t know, he worked his way up to become Assistant Chief of the colony. He worked in the colonies all his life. And I vaguely recall the prisoners writing letters, postcards and giving stuff to him. There was never any accidents with prisoners on his shift, and no one needed hospital etc. In 33 years of his career in the Ministry of Internal affairs there was not one accident. I never heard him complain. Even when he was ill, I never once saw him take a single tablet. He was diagnosed with cancer, and when they gave him chemotherapy, and it took 5-6 of us to hold him down. He never had injections, tablets, never took painkillers. He was such a healthy man, so resilient and never complained.”

How is your life in Dolinka today compared to back then?

“There used to be a woman’s prison here and Mine number 5 was here in Dolinka and on the opposite side there was a Karlag female prison. I lived in Shaktinsk, I had a 2 bed-roomed flat there but when mum became paralysed I came back to look after her, then then dad became ill with lung cancer and then I buried them both and came and lived here. I sold the flat in Shaktinsk and came here. City life doesn’t attract me any longer, I don’t know why, I like my country living now, with my allotment. I’ve just got used to it now, and then I started working at the museum. I’ve been working at the museum for the past 5 years, it’s my 6th year now. There are a lot of people coming to see us. From Italy, Germany, America, from all over, loads and loads, we had people from Poland, from Finland, and even, the Arabs, do you remember Tolik, the black ones, first time I had seen a black man. Japanese, Korean, everyone’s been here.”

“Did you or your family have any problems after the fall of the Soviet Union?”

“No, never, no one ever went after us or accused us of anything or persecuted us. We always lived peacefully. As I said, we were always getting letters, postcards, thank you notes to us, yes? Even the relatives of some of the prisoners came to visit us. Our family was always so friendly and Dad was always bringing someone home, welcomed them, gave them food, drink. No, we didn’t have any problems whatsoever and no one had a problem with us. And my father died on 28th April 2001, at 6 in the morning.”

“What did your dad thing of the break up of the Soviet Union, was he pleased or not?”

“He was against it, of course, he was very upset about it. Well, first of all when there was a Soviet Union, everyone respected each other but now no one respects anyone today! I don’t like it! Everyone is trying to take something off someone else! Lying to each other, it didn’t used to be like that before. Even now I think I would like to go back to the Soviet Union times . It was much easier to live during the Soviet times than now. My dad was a zealous communist, that’s why he was always for the Soviet Union – he was always for the Soviet Union. And I would gladly go back to those times, absolute truth, I absolutely preferred living in Soviet times.”

“These days our president…he’s ok. I wish everyone was like him – he doesn’t really bother us Russians. But look at what’s going on in places like Lithuania, Russian speakers aren’t looked after – it’s nothing like here. So – good health to our president, (Nursultan Nazarbayev which has a great reputation among ordinary people in Kazakhstan) because under him we breathe easily.

“So are these days better than before, have things improved? For you personally?”

“Well, what to say – honestly…for me? I don’t know what to say. Its hard to compare? In soviet times I would have travelled anywhere, there was always work. Now finding work is difficult…well, these days you cant say anything – we live in Karlag now! I lived ok then, it depends on you as a person, on how you act as a member of society. I lived well then but I cant say I live badly now! I liked living then and I like living now! Times have changed but I preferred living then!”