*Due to a new exciting article which has never been published in English about The Long Walk, I am republishing four articles three years after it all started on this site. These articles have covered most things and aspects of the Long Walk so far…so stay tuned for the new article coming up soon!

Leszek Gliniecki’s story

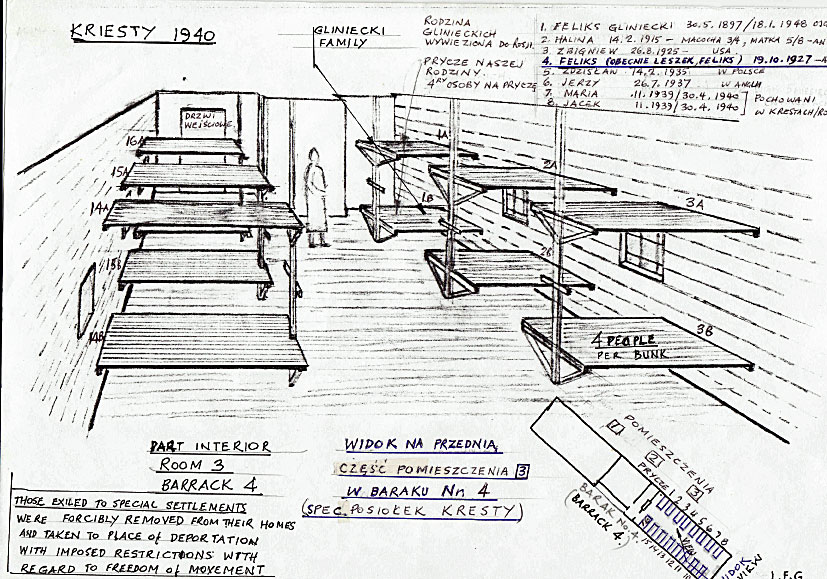

I did not go to the northern reaches of European Russia by choice. I was turfed out of my home in eastern Poland, along with my family, by Soviet forces whose aim was to carve up my homeland. While the winter of early 1940 still raged, we were exiled to a special settlement in Archangelsk Province. Families were billeted in to crammed wooden barracks and food was in short supply.

I spent 18 months in exile and 9 months of them shuttling between the settlement and a nearby village school where the Soviet authorities had decreed that what I needed was an education conducted in the language of the invader that I so despised.

Even now, more than 70 years later, I still remember that school. But, to my total astonishment, one of my fellow pupils apparently did not.

The Long Walk in Readers Digest

In May 2009 I read a piece published in Readers Digest written by John Dyson which directly related to the experience of Polish exiles in Siberia and northern Russia.

The article concerned a spectacular escape from a Siberian Gulag which was chronicled by Slawomir Rawicz in his book The Long Walk. The book claims to be a true story but there have long been doubts about its veracity culminating in a BBC Radio 4 documentary in 2006 which unearthed archive material which contradicted Rawicz’s account. Although it discredited Rawicz, the investigation also raised the possibility that the escape documented in the book could have happened to someone else.

So it was something of a sensation that John Dyson said he had found someone claiming to be the true hero of The Long Walk – Witold Glinski. Dyson’s “special feature” held out prospect of significant discovery under the title: “The real long walk – Fifty years on a mystery is solved and a hero is revealed”. It detailed Glinski’s account of the escape and gave an explanation as to how Glinski’s story could have fallen into Rawicz’s hands.

The claims of Witold Glinski

The trouble was that there were aspects of Glinski’s story which I knew were not true.

The key point is this. At the time Glinski was supposed to be a 17-year-old escaping from hard labour at a Gulag he was, in fact, with me in at the Kriesty special settlement where he was attending school, aged 14. But, and this is crucial, in addition to my eyewitness account, there is readily available archive material that supports what I say.

When I wrote to Readers Digest pointing out errors in Glinski’s account compared with official documents, I enclosed copies of Polish archives but mentioned that I also had information from British archives confirming what I said.

The author John Dyson responded that he had already seen similar documentation and Glinski did not remember me. Dyson said he had seen similar documentation to the records I had sent but Glinski, who the author had found “extremely convincing”, said such information was unreliable and “fabricated”.

He had warned his readers he had no hard proof of Glinski’s claims and did not see the need for any further disclosures.

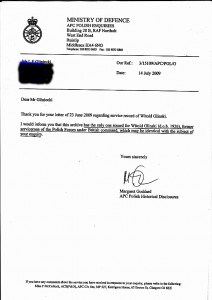

Letter from British Ministry of Defence (Polish Section) states that their archives state that Witold Glinski was born in 1926, and that he was the only one of that name in the Polish Army under British Command.

The young explorers

The Readers Digest story was followed up by media both in the UK and Poland. And in addition three young Polish explorers, who made a special trip to meet and talk to Glinski, who convinced them of the veracity of his story during a three day visit to his home in Cornwall, England.

They used the story as a rationale to recreate the escape. They wanted to spread the word that it was Witold Glinski – and not Slawomir Rawicz – who was the real hero of The Long Walk.

Their enterprise was given the honorary patronage and support of the Polish Government. They also raised sponsorship and backing from a number of leading Polish companies and organisations.

The movie

The timing of Glinski’s revelations also coincided with news that a new film inspired by The Long Walk was in the pipeline. Peter Weir, its director, re-titled it The Way Back because of his doubts about the authenticity of Rawicz’s book and has now been released.

The book by Linda Willis

Then a new development. Linda Willis, an American researcher who had found hard proof in archives to help the with the BBC expose of Rawicz, was writing a book looking into the background of The Long Walk and had done her own interviews with Glinski. It was called the “Looking For Mr Smith” – the name of one of Rawicz’s characters – and was published in November. Willis who investigates whether someone other than Rawicz had undertaken the journey reveals in the book that the she conducted interviews with Glinski in 2003 and 2006.

But so far the material I have amassed and research I have done since Glinski came into the spotlight has yet to see the light of day. I would like to present some of it now so that people can make up their own minds about his claims.

My eye witness account

My involvement in all this was initially based on the fact that the Readers Digest piece directly contradicted something I had seen with my own eyes.

I was amazed to read in the Reader’s Digest that the young teenager I was at school with in Kriesty was now being touted as the new hero of a book – which, incidentally, I had dismissed as fiction more than 20 years ago when I read it.

In the Readers Digest piece Glinski portrayed himself as the leader of the group of prisoners who broke out of the gulag just as Rawicz had done. The group included two captains and a sergeant from the Polish infantry. This is a corp of men which had long enjoyed a reputation for courage, skill and bravery, especially following the military prowess they had shown fighting for and defending Poland’s independence in 1918 and 1920. I had never been wholly convinced of Rawicz’ claim to have led these men in the way he claimed, but at least he was a 24-year-old military man – although apparently not a commissioned officer as he claimed in the book.

But the idea that men from the Polish officer corp would need to be – or allow themselves to be – led by a young teenager fresh out of school struck me as altogether beyond belief.

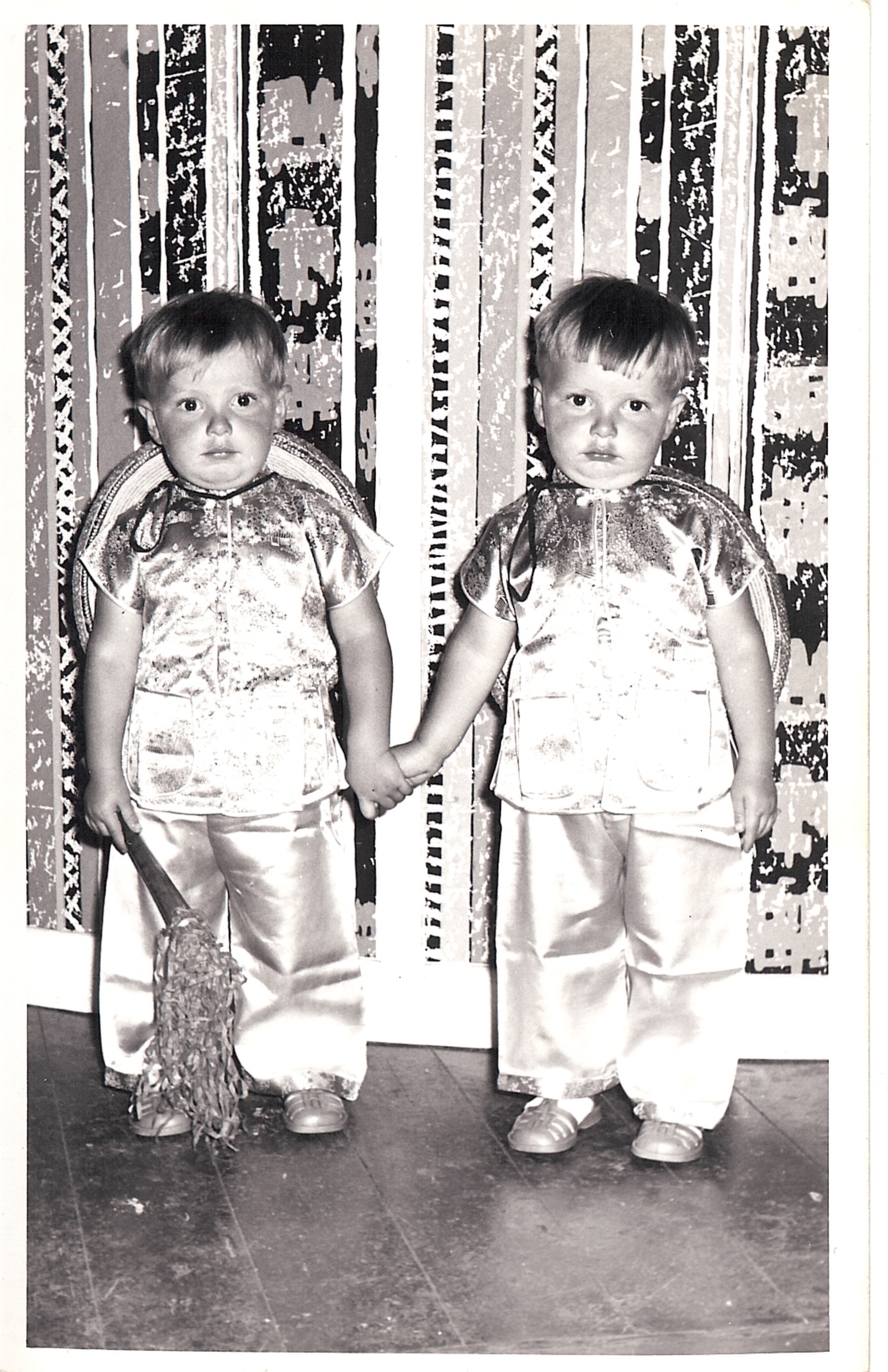

The Gliniecki Family´s Barrack number 4 in Kreisky 1940. 4 people per bunk. These were barracks for those specifically exiled to special settlements. People who were forcibly removed from their homes and deported to these places with restricted movement. These were not GULAGS.

Our school, and Glinski’s real age

For Glinski’s story to be true he would needed to have been 17 when I knew him. That would have been impossible because only exiled boys under the age of 14 at the beginning of the school year qualified to attend classes there. Any older and they would have been sent to cut trees in surrounding forests by the Soviets.

And indeed I now have three sets of archives Polish, Russian and British – where the dates confirmed what I thought. He was born 1926 and not in 1924 or any other year as he variously claimed.

I did not know him well. He and his sister Irena went to the same class – grade 5 – even though he was two years older than her. I was in grade 6 although I was younger than Glinski by one year.

The school was situated in a single storey timber building several kilometers from the Kriesty camp. During the week, myself and six other children from exiled families shared a room in a nearby village house. The room where we slept served as an all-purpose area for cooking, eating and washing. There was a wooden table and two benches which were used for dining and homework. Glinski slept in the bed next but one away from me.

Glinski did not remember me

When I wrote to Readers Digest pointing out errors in Glinski’s account compared with official documents, I enclosed copies of Polish archives but mentioned that I also had Russian archives confirming what I said. The author John Dyson responded that he had already seen similar documentation and Glinski did not remember me.

But he added that Glinski had told him that the data was wrong in several aspects: “His age is incorrect for example, though he did not know this until he was reunited with his sister in Poland a few years ago and they discovered the records gave them birthdays only a few weeks apart.”

Glinski: records fabricated to cover foul events

Glinski apparently believed “record-keeping at that time was fabricated to cover events such as disappearances and escapes of people which could not be fully explained.”

He found Glinski “extremely convincing” despite having no hard proof of his claimed exploits – a point he had included in his story. But he added there were gaps in Glinski’s memory.

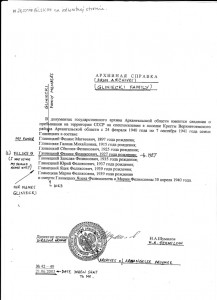

Document from Archives of Archangelsk Province stating that Witold Glinski, born in 1926, arrived at the same time as his mother, sister and brother, to Kriesty on 24.02.1940. He left Kriesty, also at the same time as his mother sister and brother, for Szachunia on 02.09.1941.

Contradictory locations and dates

During my correspondence with Dyson, Glinski made a number of contradictory claims about locations and dates. But this was the most startling to emerge: Dyson stated Glinski “worked in a gang at Kriesty preparing log-rafts for the break-up of the river ice in early spring 1941. Around February/March he went alone to Szachunia where he contacted and stayed with his father.”

Yet in the original Reader’s Digest piece Glinski was escaping from the Gulag in Yakutsk in February 1941. Szachunia is 5000 km away from Yakutsk. He could not be in both places at once. Yet, despite all my efforts to persuade him, Dyson did not see the need to publish a correction.

The upshot was that Dyson and The Readers Digest did not feel that there was any need to publish any form of correction.

Major discrepancies

There are so many contradictions between Glinski’s accounts to different people and the archives that it is hard to know where to begin. But let’s start with an extraordinary discrepancy between what he told John Dyson and Linda Willis.

Let’s start with his age. He tells Willis he was 15 in 1940 making his birth date 1925. In the Dyson piece he was 17 when in Moscow’s Lubianka prison where although no precise date is specified, it is clear that the episode happened sometime between the Russian invasion of Poland in September 1939 and his arrival near the Yakutsk Gulag in autumn 1940. This would make his date of birth either 1922 or 1923.

Readers Digest/Linda Willis: separate accounts

But the really striking thing is that in the Linda Willis story there is absolutely no mention of the Lubianka episode which was to condemn Glinski to hard labour in a Gulag. There is a fundamental contradiction between his two separate accounts of events leading up to his incarceration in the Gulag from which he later supposedly escaped.

In the Readers Digest version, much is made of a scene in Moscow’s Lubianka prison where Glinski says he was interrogated – much the way Rawicz supposedly was – then sentenced to 25 years hard labour. From there he does a few stints in work camps before arriving in Irkutsk then marching 1,800 km north east to the Gulag.

In the Willis book the Lubianka scene describing how Glinski became a convicted criminal can not possibly fit in the way that it is described in the Readers Digest.

Willis does mention that Glinski was detained and sent to an unspecified Russian prison soon after being rounded up by Russians forces when they first invaded Poland. But, crucially, Willis also says he was not sentenced to hard labour. In addition, Glinski tells her he followed his family in to exile the Arkangelsk settlement which would not have been possible if he had been a convicted criminal.

Map shows the normal route all Poles would take to get out of Russia, into Tashkent area -Caspian Sea – Pahlevi (Persia) as against Glinski’s route to Irkutsk, away from the exit area for Poles, the Polish Army, and Poles generally.

Getting to Yakutsk

So how did he end up in Yakutsk according to the account he gives to Willis? Glinski still gets to the Gulag via Irkutsk, as stated in the Readers Digest story. But this time he arrives there as a free man on a train. He ends up being taken into captivity and marched to the Gulag not because of some unstated crime punished by officials after a harsh interrogation at the Lubianka, but because the authorities simply want to “make up the numbers” of a group of prisoners who happen to be heading for Yakutsk at the time.

Glinski tells Willis that he considered that he and hundreds of other entirely innocent passengers that were rounded up and shipped to the Gulag were “fair game” because they had no travel documents.

Document from Polish archives of the Institute of National Remembrance in Warsaw stating that Witold Glinski, born 1926, arrived at the same time as his mother, sister and brother, to Kriesty on the 24.02.1940, and left Kriesty, at the same time as his mother, sister and brother, to Szachunia on the 07.09.1941. And also that the Gliniecki, family including myself, arrived at Kriesty on the 24.02.1940 and left on 07.09.1941.

Archives: Glinski did not arrive alone

Setting aside this massive contradiction, and now taking the Willis book in isolation, I also have serious doubts about the credibility of Glinski’s account of events.

At the start of the Russian invasion he tells Willis that, along with other students, he is rounded up, interrogated and boarded on a train destined for one of Russia’s prisons. So he is separated from other members of his family who make a direct journey to exile at Kriesty.

But he also tells Willis that although he was arrested, he was not convicted of anything and would not have to go to a hard labour camp. That meant he was later able to follow members of his family already interned at the Arkangelsk settlement which was meant for exiled Poles but was not suitable for criminals.

However, this contradicts archive information which states that Glinski arrived at the settlement at the same time as his mother, sister and younger brother and not sometime later.

Presence in a second camp makes no sense and is left unexplained

Another contradictory feature of his account concerns his claim that after Kriesty he was sent to a special settlement in Gorkowskaja Province in 1941. But this cannot fit in with information in the archives about when he was freed by the Russians and allowed to evacuate the country.

The Russians changed sides in September 1941 at which point the exiled Poles were given an amnesty. The paperwork shows Glinski’s amnesty came while he was in Kriesty. So his presence in a second camp in 1941 does not fit in and makes no sense. His reason for being there and the circumstances and timing of his departure from this camp are left completely unexplained in his account to Willis.

Document from the Archangelsk Archives stating that my family, and I, were in Kriesty from 24.02.1940 to 07.09.1941.

Leaving Russia in the wrong direction

A further anomaly concerns the way he finally chose to evacuate Russia after he was amnestied. Glinski elected to get on a train going east to Irkutsk on advice from his father.

But going east through Irkutsk out of Russia was not something which amnestied Poles would have done. It takes you in the direction of China on a route which no exile I have ever come across has claimed to have taken.

The overwhelming desire at that time was to head south to where the Polish army was forming. Polish men and teenage boys wanted to make themselves available for any effort to win back their country. But Glinski apparently went east on his father’s advice. That advice, unfortunately, was left unspecified.

Impossible timeline

Finally the one of the most unbelievable aspects of the account Glinski gives to Willis is linked with the time line implicit in his story. He was in amnestied in Kriesty in September 1941 and even claims he was somehow sent to a second camp after that. Yet he has to get to Persia by early 1942 to fit with information given in his own military records as revealed in Linda Willis’ book.

And this is where we get to the very core of this entire saga. As I’ll demonstrate later, to fit in the Long Walk within this timeframe – plus cover all the other ground he describes in his account to Willis – is absolutely impossible.

Media vs. archives

Here are some more inconsistencies between the archives and what Glinski told Dyson and Willis.

Reader’s Digest: (correspondence): Glinski left Kriesty before amnesty announced

Archives: He was at Kriesty when amnesty was announced on 2 September

Reader’s Digest: In the autumn/winter of 1940 Glinski walked from Irkutsk to Yakutsk.

Archives: He was In Kriesty between February 1940 until September 1941.

Reader’s Digest: In February 1941 Glinski escapes with 6 others from his gulag.

Archives: He is still in Kriesty 5000km away.

Willis: Glinski followed his family to a special location in Archangelsk Province

Archives: Glinski arrives at Kriesty at the same time as other family member

Willis: Glinski was 15 in 1940, hence born in 1925.

Archives: All 3 available public archives state he was borne in 1926.

The Archives Story

If Glinski is the real hero of the Long Walk he would have had to have undertaken an incredible 11 month 6,500 thousand kilometer trek from a hard labour Gulag in Siberia going south to Calcutta sometime in the early 1940s. It involves traversing a snow-swept Russia, followed by legs through Mongolia and the Gobi Desert, China, Tibet and the Himalayas into India.

But if one discounts all Glinski’s claims and recollections and simply looks at the historical documents that have come to light so far, this is the picture that emerges.

Following Russia’s invasion of eastern Poland in September 1939, Glinski was exiled to Kriesty in northern Russia in from the 24 February 1940 until 2 September 1941 when he was released with travel documents to Szachunja.

Glinski’s personal military records, as described by Linda Willis in her book, pick him up in March 1942. He was then recorded being evacuated to Persia – as it then was – with the Polish Army in April 1942.

This would leave around 7 months for him to travel from Kriesty via Szachunia south to the port of Krasnowodsk on the Caspian Sea from where Polish Army units were embarking for Pahlevi in what was then Persia.

This would fit in well with the type and duration of journey that was typically made by exiled Poles after they were amnestied and fled south from Russia joining newly formed Polish Army units on the way

But it is absolutely impossible to fit Glinski’s claimed exploits in to this allotted 7 month gap.

During this time he would have to cram in not just the 6,500 km Long Walk from a Siberian gulag to Calcutta which by itself was supposed to take 11 months. In addition there would be the time to travel 7,000 km to the gulag from Kriesty, then recuperate and plan the escape. And then there is the leg of the journey he needed to make after the Long Walk was completed. In Calcutta he would have rested then embarked on the 4,000 km journey back to the Caspian Sea. Then by boat to Pahlevi, another 200 km.

Which is more likely given what else has come to light? Glinski’s claims of a spectacular escape based on his word alone? Or did he simply evacuate Russia in a manner typical of other amnestied Poles which would fit in well with what the archives point to?

Why it matters

The story of Glinski’s supposed heroics has spread far and wide on the basis that it is somehow credible when it is not. On closer inspection there is not a shred of hard evidence to support his claims and plenty of solid evidence that he is not telling the truth. And yet there have already been consequences that deeply troubled me as Glinski’s claims gained traction in the public domain.

Following the Readers Digests “revelations”, three young Polish explorers intrinsically linked his emergence with their project to re-create the Long Walk. One of the explorers, Tomasz Grzywaczewski told the Swedish writer and explorer Mikael Strandberg on this site: “Our aim was to show that the real hero of the Great Escape was a Polish man named Witold Glinski. Not Slavomir Rawicz.”. The expedition garnered the backing of Poland’s Foreign Minister, Radoslaw Sikorski.

This troubled me deeply. I wrote an open letter to Mr Sikorski warning of the dangers of being associated – through this project – to a man whose stories did not add up. Amongst other things I was told that support for the project was justified because it helped raise the profile of the plight of Siberian exiles in the Second World War.

This is a very laudable aim and one I fully support. I, like many others who were there, feel that the plight of exiles in Siberia and northern Russia is not well known or understood. There was enormous striving and hardship. The graves of those who died thousands of kilometers away from their homeland were left overgrown and unmarked with no-one to tend and visit them. As a modest contribution, I myself provided information and plans from which our forgotten cemetery at Kriesty was located, cleared and commemorated.

But heroes need to earn their status – it’s not something that should be lightly given. There was plenty of real courage, bravery and fortitude exhibited by Poles during that period. Why allow that to be overshadowed by Glinski’s unsubstantiated tales – or Rawicz and his Long Walk fiction for that matter?

Leszek Gliniecki was born in 1927 near Grodno. This area is now part of Bialarus after parts of eastern Poland were sliced off when borders were redrawn following the Second World War. He has not seen the districts where he was born and grew up since being snatched away by the Soviets in 1939 and the new border arrangements make any such trip difficult.

His father was a forestry administrator heading up various districts in eastern Poland at a time when timber was one of Poland’s leading economic activities.

In October 1939 he and his family were turfed out from their home by the Soviets, and on the 10th Feb.1940 forcefully exiled to a special settlement called Kriesty in Archangelsk Province of northern Russia. Over the last 20 years he has been collating historical maps of Russia and researching other information in order to get a better understanding of his family’s movements and experiences during and following exile. Three and a half years ago he instigated a project to find and re-establish the cemetery in Kriesty where – amongst many others – two infants in his family were buried shortly after being exiled to the camp in February 1941.

He researched archive information to locate Kriesty which no longer appears on modern maps. He also made sketches and plans based on his memories of the camp that proved crucial in locating the cemetery which had long since become an indistinct area of scrub and woodland. It has now been cleared and enclosed.

He has friends among local Russian people who, along with local schoolchildren, helped out with the project. Many of their families were internally exiled to the area by the Soviet authorities.

He also researched archives information to provide information for a commemorative plate, unveiled earlier this year, which remembers all the names of those who died in Kriesty – thousands of kilometers away from their homeland.

Leszek Gliniecki is retired and living in London, England.

I’ve just featured The Long Walk in a graphic novel called Dawn of the Unread and after much consideration am less concerned with whether or not Slavomir Rawicz’ or any other prisoner ‘actually’ did it and more with the effects of the story. The writer who has illustrated the story (John ‘Brick’ Clark) was so inspired when he read it in a boarding school that he went on to travel the world, writing about his journeys, before becoming a political cartoonist intent on making a difference. It’s so difficult to judge the validity of such stories as it is impossible for those of us who have not experienced war to have any idea of the psychological effects. But of course, we can’t also build our history on false memories. I think the war created a kind of collective consciousness in which stories and truths got mashed together.