When I agreed to take a job in northern California as a mountain biking guide, I was excited about the opportunity to ride every day in the beautiful Sierra Nevada Mountains. Further sweetening the deal was the fact that I had two free weeks in my schedule before my contract was to begin. My thirst for adventure was handed a new opportunity.

I do not live in California, and I do not own a car. I ride my bicycle or walk everywhere I go. With a bit of haste, I decided to fly from New Orleans to San Diego with my bicycle and ride for two weeks to the resort where I would be working. This last-minute adventure planning was exciting, and a big change from my last big bicycle tour.

In 2011, I was a US Peace Corps Volunteer living in Ethiopia. When my contract ended, I traveled north to Lake Assal, Djibouti by bus. The nearly lifeless lake sits at the northern end of the Great Rift Valley and its shores are the lowest point of land on the African continent. From there, I cycled 3,000 km through Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Tanzania to the base of Mount Kilimanjaro, then trekked to the summit of Africa’s highest peak. The journey took 68 days.

I planned my African adventure for more than a year. I had a planned route, and dozens of backup routes. I bought gear, trained my body, studied languages, read all the relevant Lonely Planet chapters, and spent hours on the Internet connecting with Couch Surfers and reading other cyclists’ blogs. I obsessively researched past expeditions in a quest to legitimately claim that I was the first person in history to do this, which felt like an important detail to me at the time (South African cyclist Riaan Manser visited both Lake Assal and Kilimanjaro during his circumnavigation of Africa, but he took a side trip by car to the mountain since it is not near the coast). Planning the trip consumed a great deal of my time and energy, leaving me unable to focus on much else.

The expedition was also a fundraiser. I had worked with a children’s center in Bahir Dar, Ethiopia that needed funds to expand, so we partnered together to raise $4,000 USD through donations. Raising funds meant constantly updating my blog with photos and stories to keep interest and spread the word. It also meant that people were watching, creating some self-imposed pressure on me to complete every single inch of movement with my own power. The stakes were high, as was my stress level.

In the end, Low2High: Africa was a total success. I completed the journey, and I raised an extra $1,000 above our goal. However, some negative effects reverberated in me for long after. I returned to the US unable to focus on daily life. My head was still on the road, chasing the ever-ascending horizon. This led, in part, to a long relationship falling apart, and an inability to reconnect with my own culture. The subject of my obsession was now in the past, and I became lost. I felt like I had caught the White Whale without ever thinking about what would come after.

After recklessly fleeing to the Philippines, and with a lot of help from friends and family, I eventually put my life back together. My desire for adventure was still very strong, but I had become much more cautious. I learned some lessons from that expedition, and I applied them as best as I could to this new ride.

I didn’t plan anything apart from the start and end points. I have a friend from the Philippines in San Diego, so that was my starting point. I had to be in Sequoia National Forest for work, so that was my destination. The rest was intentionally loose and flexible. I didn’t allow myself to obsess over details or plan where I would sleep. I simply left San Diego heading north along the Pacific Ocean coastline.

Flexibility made the trip very enjoyable. I stayed with contacts in Los Angeles, San Luis Obispo, Santa Cruz, and Fresno, but never set fixed dates. I rode until I got tired or found a pleasant place to stay for the night. I camped in State Parks, and even slept next to a hidden waterfall after receiving a tip from a gas station clerk. I saw the ocean every day, met other cyclists, saw foxes and elephant seals, and had wonderful conversations with strangers along the way. I felt much more open to experience every single day as it came. Unlike my ride in Africa, I wasn’t tracking distance or taking photos of every little event for an Internet audience comprised mostly of strangers. In fact, the only photos I took were with my iPod. I was content being myself, on a bicycle, surrounded by beauty.

The ride in California proved easier than Africa for many reasons. Factors such as weather, language, infrastructure, communication, nutrition, and comfort all seemed improved, even if only by comparison to the challenges of the Horn of Africa. However, the greatest improvement was internal. I was open to people I met, and I was playing it safe. Poor visibility and incredibly gusting winds north of Big Sur convinced me to hitchhike to Santa Cruz. The experience turned out to be yet another wonderful memory. I was picked up by a young couple heading home to San Francisco who told hilarious jokes and went out of their way to drop me off in Santa Cruz.

Hitching a ride didn’t bother me. I didn’t feel like a failure or a cheater. The goal was to have fun and never compromise my own safety. I would have been unable to do that if I were stubbornly adhering to rules I set for myself for the sake of bragging rights down the line. To appease my obsessive nature, I cycled east the entire 350km from the coast in Santa Cruz to the resort, gaining 2,200 meters of elevation in the process, but it didn’t matter. I had discovered that I could be less hard on myself and enjoy life in the slow lane for a few weeks.

To an outsider, the accomplishments of this ride may pale in comparison to two months in Africa. There was less danger, unimpressive statistics, and no fundraiser. There was no triumphant final step onto the summit of a glaciated volcano to mark the end of an epic journey. When I finished this ride I met my new bosses, took a shower, and started work for the day. There were no comments from strangers on a blog to make me feel good about what I had already done, but I felt absolutely great regardless. I had overcome some hurdles of my own character and arrived ready to live my post-expedition life in my new surroundings.

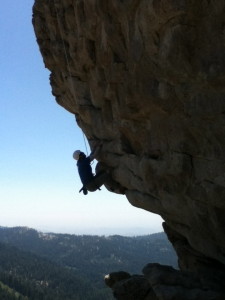

Kyle Henning is a mountain biking and rock climbing instructor at Montecito Sequoia Resort on the borders of Sequoia National Forest and King’s Canyon National Park in California, USA. His blog from Africa is available at http://low2highafrica.blogsot.