The greatest ocean rower ever

Since I published two extremely well read articles about the dire straits of an explorers life, the One meeting Arita, and the one written by CuChullaine O´Reilly, I have literally received 9 emails from people with stories about forgotten heroes. The most amazing one is about a Swede who, before it became as popular today, crossed the oceans in a little boat. His name is Anders Svedlund and he died a kind of a tragic death, when he, disillusioned with life, cornered in a city, far away from open nature, stood up on a chair to change a light bulb in his apartment in Auckland, New Zealand, and fell, hit his head against the table, and….died.

I know three ocean rowers today, two very brave ladies, Roz Savage and Sarah Outen, and than a personal favorite explorer of mine, Erden Eruc. It is just recently I kind of have been involved in ocean rowing, even if I met Roz back in 2002 at a friends place in London. Since I am born in an area surrounded by forest, lakes, rivers, moors and tarns, the ocean has always been very scary to me. However, my points of this article is three, first, ocean rowing has become a big thing, with big income today within the exploration business, secondly, they really have great boats today and thridly, in the light of this Anders Svedlunds rowing seems extra ordinary! And it is time we other explorers try to highlight the people who did great things, but never got a lot of attention. Basically because that wasn´t such a great interest for them. But what personalities!

I found this great story about Anders Svedlund on the Internet:

We first met Swedish born, neutralized Anders Svedlund in July 1974, when he quietly stepped ashore from his plastic five-and-a-half-metre boat right in front of our home here at Papehue, on the west coast of Tahiti, during a truly epic trip across the Pacific. The sole reason why Anders repeatedly escaped to the sea was his love of nature, and the peace of mind he experienced when lost in the solitary contemplation of it.

Unlike Peter Bird, he cared very little for records, shunned all publicity, and never kept a log or wrote down the story of his accomplishing the amazing feat of rowing across the Indian to Madagascar in 64 days, he went straight back to Auckland, and, without telling a soul where he had been, resumed his old trade as a house painter.

After three years – the time it took him to save enough money – he set out again on what was to become an even greater adventure. The point of departure was Huasco in Chile, which he left on February 27, 1974, at the oars of the same old plastic boat he had : used for his Indian Ocean trip, but now renamed Waka Moana.

His only aim was to follow the sun for as long as he could. He rowed with such determination, however, that he sighted his first Polynesian island after only two months. Since he had no navigational instruments, and it was uninhabited, he never found out its name. But he didn’t at all mind being alone on land for a change, and managed to pick and open a few green coconuts.

The next island he came across seemed on the contrary to be definitely over-populated, and was full of weird concrete buildings. It was the top-secret Moruroa, a nuclear testing base.

But the French pilots and navy men patrolling the area never imagined for a moment that people could come all the way from South America in a small boat of the sort they used for fishing and fun. So he rowed all day unnoticed along the northern coast of the island, within shouting distance of the shore. Moruroa is situated at 22 degrees south latitude, and Anders made the mistake of trying to reach the Austral Islands still further south, which involved him in a losing battle against “strong westerlies. Luckily for him, the captain of an inter Island cargo boat, whom he encountered at Rimatara, took pity on him, and brought both him and the Waka Moana to Papeete, whence he rowed on the calm lagoon waters out to our home.

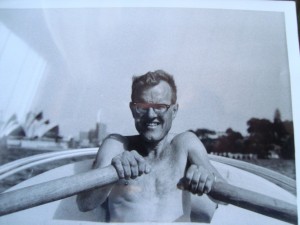

We immediately took a great liking to Anders, whose only fault was his excessive modesty and gentleness. He devoted his first week in Tahiti to mountain-climbing which he considered the best way “to stretch old sealegs.” But we cornered him eventually, and got very straightforward answers to some questions that had long intrigued us.

For example, he had no radio and no books, so we suspected he must have felt mightily bored at times. No, he said, the sea offered a splendid, everchanging spectacle, which he never tired of watching. It actually made him so happy he often burst into song. Mostly he sang old Swedish folksongs he had learnt as a child. He could go on singing for hours. He made up poems, too. Or he discussed philosophical and religious problems with himself.

We were equally interested however in the more practical sides of his spiritual quest, among other things how much sleep he managed to get. Anders assured us that he slept very soundly for 10 hours a night. He slept on a mattress in the forward “cabin” which was so low that he had to crawl in and out of it.

He added that Waka Moana, when left to her own devices, had a most fortunate propensity to turn her nose to the wind, which prevented her from capsizing. The one thing he regretted was that she heaved and rolled so much that it was absolutely impossible for him to stand on his head for any length of time. To function normally one must stand on one’s head for at least an hour a day, he said.

During his first rowing adventure in the Indian Ocean, Anders had equipped himself with a kerosene stove. But it didn’t work well, and he soon ran out of kerosene. This time he made all possible space available for the storage of food. When he left Chile he had in his aft cabin 250 kilograms of flour made from roasted South American quinoa wheat. It kept better for having been pre-roasted, he said. Twice a day he mixed this flour with water to make cold porridge. He also carried a good supply of honey which he poured over the porridge. For desserts, he had about 50 kilograms of dried fruit. His water supply did not exceed 300 litres. But he had been able to catch some rain water.

Finally, he took the wise precaution of swallowing a vitamin C tablet every day. What surprised us most was that Anders had no fishing gear. But the explanation was simple: he was a vegetarian (and a teetotaller, as well).

When, at the end of July, Anders decided to continue his voyage, we gave him what we considered a most appropriate farewell gift: a sackful of green, slow-ripening grapefruit, likely to last him for several weeks. With this last sack loaded aboard, the weight of the water and food supplies was over 600 kilograms. Since the canoe itself weighed 360 kg, it was more than a ton that Anders had to drag across the ocean with the help of his two tiny oars. It was not without serious apprehension that we watched the heavily loaded Waka Moana confront the choppy seas outside the reef and disappear in a westerly direction – “towards Australia,” as Anders himself in very broad terms had formulated his sailing direction and destination.

As we learned two months later, Anders had kept rowing in his usual style towards the setting sun at an average speed of about 40 miles a day. But he eventually had to give up – because of our grapefruit!

They simply did not agree with his accustomed diet of cold porridge, and before he could bring himself to throw them overboard he was suffering from chronic colic which caused him such severe pain that he had to put into Apia harbour. His date of arrival was September 9, which meant that his whole Pacific trip had lasted six and a half months.

We saw Anders a few years later in Auckland. It was obvious from his dejected air that the sort of urban life he was then leading made him even sicker than our Tahitian grapefruit had.

His solution was, of course, to go to sea again. But before he could do so, quite unexpectedly, he set out on another, much longer, voyage, as related by the following brief item in an Auckland newspaper of April 23, 1979:

OCEAN ROWER DIES !N KITCHEN: Anders Svedlund, who achieved international fame in the early 1970s for two marathon solo rows across thousands of miles of open ocean, died on Friday night after a fall in his kitchen. The police first thought that he might have been shot. But a post-mortem examination established that lie had struck his head on the side a table following a fall.