What would we lovers of the Russian Far East do without Moki Kokoris and her knowledge of this area? It is an honor for me to present to you, for the third time, this extra ordinary woman from Ukraine and her knowledge about the Far East. This time she writes about the Dolgans and their Mammoths. An article which open horizons, gives new knowledge and makes me want to return immediately!

Mammoth tusks where a subject much talked about during my journey along the Kolyma back in 2004-05 and quite a few of the Russian trappers we met, not locals, had made a living selling tusks they´ve found in particularly streams whilst trapping. They sold them to a middle hand in Yakutsk,who saw to that they ended up in Moscow, I remember they said.

The Dolgans and Their Mammoths

By

Moki Kokoris

As we continue the series about the indigenous peoples of the North, this article will introduce one of the lesser known groups of central Siberia, specifically the Dolgans.

Rossiyskiy Sever, or Russian North, extends across a distance of 6,000 km from the Finnish and Norwegian boundary through the Urals and Siberia to the Bering Strait and the Pacific Ocean. It encompasses vast areas of taiga (boreal forests), tundra (treeless wetlands and pasture lands), and polar deserts. The north-south extent of this belt widens from about 1,000 km in Europe to nearly 3,000 km in central Siberia and the Russian Far East. Siberia alone covers approximately 70% of the territory of the Russian Federation which speaks to its vastness.

Approximately 20 million people inhabit this vast expansive area, mainly concentrated in towns and settlements along the rivers and in industrial centers. Only about 180,000 of them belong to the approximately 40 aboriginal groups – the indigenous peoples of the Russian North. The majority of them live in small villages close to their subsistence areas where they still pursue traditional occupations like reindeer husbandry, hunting and fishing.

As in many other regions of the world, the Russian North has been subject to migration of peoples throughout human history. Despite their diverse historical, ethnic and linguistic backgrounds, these groups had to adopt subsistence lifestyles when they arrived in the Subarctic and Arctic regions. Although their cultural relations are poorly documented, it is known that until ca. 2,000 years ago, the North was dominated by ancient Siberian tribes. Distinct variations developed dependent on endemic fauna and climatic zones, sometimes even within the same ethnic group.

Coastal cultures emerged in areas with significant sea mammals (walrus, whales, seals), particularly along the shores of the Pacific Ocean, the Sea of Okhotsk and the Bering Strait (Aleuts, Yupik, coastal Chukchi). River cultures were more prevalent in the Far East. The Nanai, Ulchi, and Udege of the Primorye area of the Far East, and also the Kets who live near the Yenisey River, were predominantly known as the fishing peoples.

The tundra and taiga cultures, however, were more widespread and occurred throughout the Russian North. Their basic traditional occupations were reindeer-herding, hunting, trapping, fresh-water fishing, and gathering. Unlike the other groups, these people were nomadic or semi-nomadic which often led to the mixing of one or more cultures into a new one. The Dolgan people are probably the most recent example of the formation of an independent ethnic group in Russia. Their consolidation began as late as the nineteenth century.

From the seventeenth century onward, the “Great Russian Road,” also known as the Khatanga Tract, existed across the Taymyr, the peninsula in Siberia that forms the northernmost part of mainland Asia. Along this tract communications were maintained by means of reindeer and dog transport between the Dudino settlement and Lake Piasino, then eastward to Khatanga and as far as Yakutia. Winter camps along this road were relatively permanent. It was in this stretch of territory that groups speaking different languages, diverse in origin, with different traditions and beliefs and different material and spiritual cultures, developed a unitary self-consciousness, language, and culture, and eventually coalesced into the Dolgan people, their collective name ‘dulghan’, meaning ‘people living in the middle reaches of the river.’ Their ethnicity is a combination of the Evenks, Yakuts, Tungus, Enets and some Samoyed. Anthropologically, they belong to the North Asiatic group of the Mongolian race. The present language of the Dolgans is closely related to Yakut, yet they consider themselves to be a separate ethnic group. The population is said to be little more than 7,000, approximately 6,000 of whom speak their native language fluently.

Currently, the Dolgans inhabit eastern territories of the Taymyr Peninsula, the Khatanga and Pyassina river basins, and to a lesser extent, the Dudinka district. All of these regions typically experience severe winter conditions with -60o C temperatures and winds of 120 km per hour. Anecdotally, Oimyakon in Yakutia, the coldest documented settlement on Earth, is known as the “Pole of the Cold,” where the mercury commonly drops to -70o C.

Still following their traditional nomadic lifestyles, the Dolgans are reindeer breeders and hunters, living in baloks which are small rectangular structures covered with reindeer skins. At 3 by 4 meters in size, they are just large enough to fit on sleds that are pulled by up to six pairs of reindeer as their owners travel across the vast tundra in search of new pasturing locations. A balok houses an entire family. Inside each balok there are two or three beds, a table and a wood stove, yet even with the stove burning wood at full capacity, the interior temperature of these movable huts rarely rises above 15o C in mid-winter.

For toddlers, the Dolgans use sled-cradles that are placed amongst the reindeer which provide welcome warmth. During the winter, the Dolgans wear thick overcoats, made from reindeer hides combined with other skins such as Arctic fox, and beautifully decorated with intricate beaded geometric designs. Applied art includes mammoth bone carving and embroidery. The Dolgans’ only musical instrument is the jaw harp.

Their economy is primarily based on hunting—wild reindeer in the north, elk and mountain sheep in the south. Subsidiary game are ptarmigan and hares. In the summer, molting geese and ducks are also taken. The semi-domesticated reindeer are raised to serve as mounts, for milking and for transport.

Although their adopted Christian faith continues to combine old animistic beliefs with today’s holiday traditions, the Dolgans still follow the Evenk calendar which is divided into fours seasons with 13 Bega (lunar) months, each named according to the traditional activity at the given time. For example, Gobchon-Bega means hunting moon, Syru-Bega is reindeer buck moon, Keta-Bega is the salmon moon, and Sigal-Bega is the moon of hunger.

Originally, the Dolgans were shamanistic. They believed that the shamans could guard them against evil spirits, called abaasy, who were thought to cause sickness by entering a person’s body and gradually devouring the individual’s soul. Other benevolent spirits, called ayy, were thought to dwell in odd-shaped stones or antlers. Dolgan shamanistic practices were nearly identical to those of the Evenks, and like the latter, the Dolgans buried their dead in the ground after the spring thaw. Sometimes a reindeer was ritually slaughtered over the grave.

As among the Yakut, the Dolgan people greatly revered storytellers. They particularly favored animal tales that told about the origins of the different clans. The Creator Mother of the Dolgans was Mammoth – Heli. According to the myth, the world was originally very small, mostly covered by water with insufficient land on which to pasture the reindeer. So the people complained to Heli. The Mammoth wandered about in the water and found Dzhabdar, the Serpent, and persuaded her to help dry the world and create more land. Heli then plunged her tusks into the sediment under the water and brought up clay, sand and stones. These became the mountains and the cliffs. The Serpent then wriggled into the new formations, creating rivers which dried out the land. This story is perhaps why the mammoth is still considered to be the sacred beast. However, it is the real woolly mammoth of the last Ice Age that thousands of years after its extinction still helps these indigenous tribes earn a living.

Today, as do all other indigenous peoples of the Arctic, the Dolgans face environmental issues in their remote North. The nickel, copper and cobalt factories of Norilsk are contaminating the regions traditionally relied upon for reindeer husbandry, and overhunting is decimating the last herds of wild reindeer as many Dolgans turned from herding to hunting. The increased use of snowmobiles in the tundra is an added factor of pollution and human pressure on the pristine environment. All of these relatively new conditions are forcing the people to seek new sources of income and livelihood.

As a result of climate change, warming temperatures are exposing the fossilized bones of valuable prehistoric fauna such as mammoths and woolly rhinos. Finding these bones is not at all unusual for the nomadic native people of the region. Roaming the land with their reindeer herds, they often come across partial skeletons.

In some areas of the Taymyr, due to the rapid thawing and breakup of the permafrost, the bones pop up to the surface at every few meters. Recent bans on elephant ivory turned Japanese and Chinese markets toward fossilized mammoth ivory for which private collectors and institutions will pay generously for the best specimens. Russian traders pay $8-156 per kg of mammoth bone, but curled tusks, some up to 5 meters (15ft) in length, are the most highly priced specimens. If lucky enough to locate good-quality bones, a Dolgan can earn as much as $7,800 in just one day, the equivalent of one year’s income by conventional means.

Still, it is the Russian traders themselves who make most of the money since private collectors will pay up to $20,000 for a well preserved mammoth tusk. A complete skull in excellent condition is valued at $30,000, while an entire reconstructed mammoth skeleton can fetch between $150,000 and $250,000.

Although the remains of many mammoths have been discovered, none has excited the public’s imagination like Siberia’s “Jarkov Mammoth”. Its massive tusks found in 1997 by the 9-year-old boy of the Dolgan family, Jarkov, this mammoth was determined to be about 47 years old when it died almost 20,400 years ago after getting stuck in thick clay at the bottom of a pond.

A French mammoth-hunter, Bernard Buigues, spearheaded the project to recover the Jarkov Mammoth. In September, 1999, introducing a new technique, the CERPOLEX / Mammuthus team excavated a huge block of frozen sediment that likely contained the remains of the mammoth. This 23-ton block of permafrost was successfully airlifted by an MI 26 helicopter and placed in a sectioned off portion of the underground network of service tunnels in Khatanga, about 250 km south of the locality (Bolshaya Balakhnya River) where the Jarkov Mammoth had been discovered. The goal of the team was to defrost the frozen block in the safety of the ice tunnel and to extract and document data from the sediment as well as from the mammoth’s remains.

In following field campaigns, the team collected thousands more fossil bones at several other localities on the Taymyr Peninsula. Another block of ice, weighing approximately 1,100 kg, containing a hind section of the Fishhook Mammoth, was brought to the same ice tunnel for further study. This block was cleaned in the summer of 2000. Part of the skeleton was still in anatomical position, and among other bones, six vertebrae thoracalis, two vertebrae lumbalis, and sixteen ribs were exposed. It became clear that some of the soft tissue had been preserved inside this block of frozen sediment, including remains of the stomach and its contents which could provide significant scientific data.

Scientists attending a conference held shortly thereafter in Rotterdam declared that the Khatanga ice tunnels, their constant temperature of -11° to -15°C, were the best place to keep these late Pleistocene faunal remains in the optimum state of preservation for future research (radiocarbon dating, DNA extraction and sequencing research) such as the Woolly Mammoth Genome Project initiated by Penn State University. The ethical ramifications of the possibilities aside, if only Michael Crichton could have stayed with us long enough, he might have witnessed the first example of cloning that could yield a real live representation of his Jurassic Park storyline, thereby removing the “fiction” from “science fiction.”

Let’s hope that the Dolgans – who along with their fellow indigenous groups that still inhabit the Arctic North, continue to rely on their unbelievable endurance, and fight tenaciously for their cultural survival – do not follow in the muddy footsteps of the woolly mammoth into extinction….

Moki Kokoris holds the position of Main Representative for the World Federation of Ukrainian Women’s Organizations NGO in consultative status with the UN Department of Public Information and she is the founder of “90-north” — a 2007-2009 International Polar Year sanctioned multidisciplinary outreach educational program offered to students and teachers studying issues and topics relating to Arctic and sub-Arctic regions.

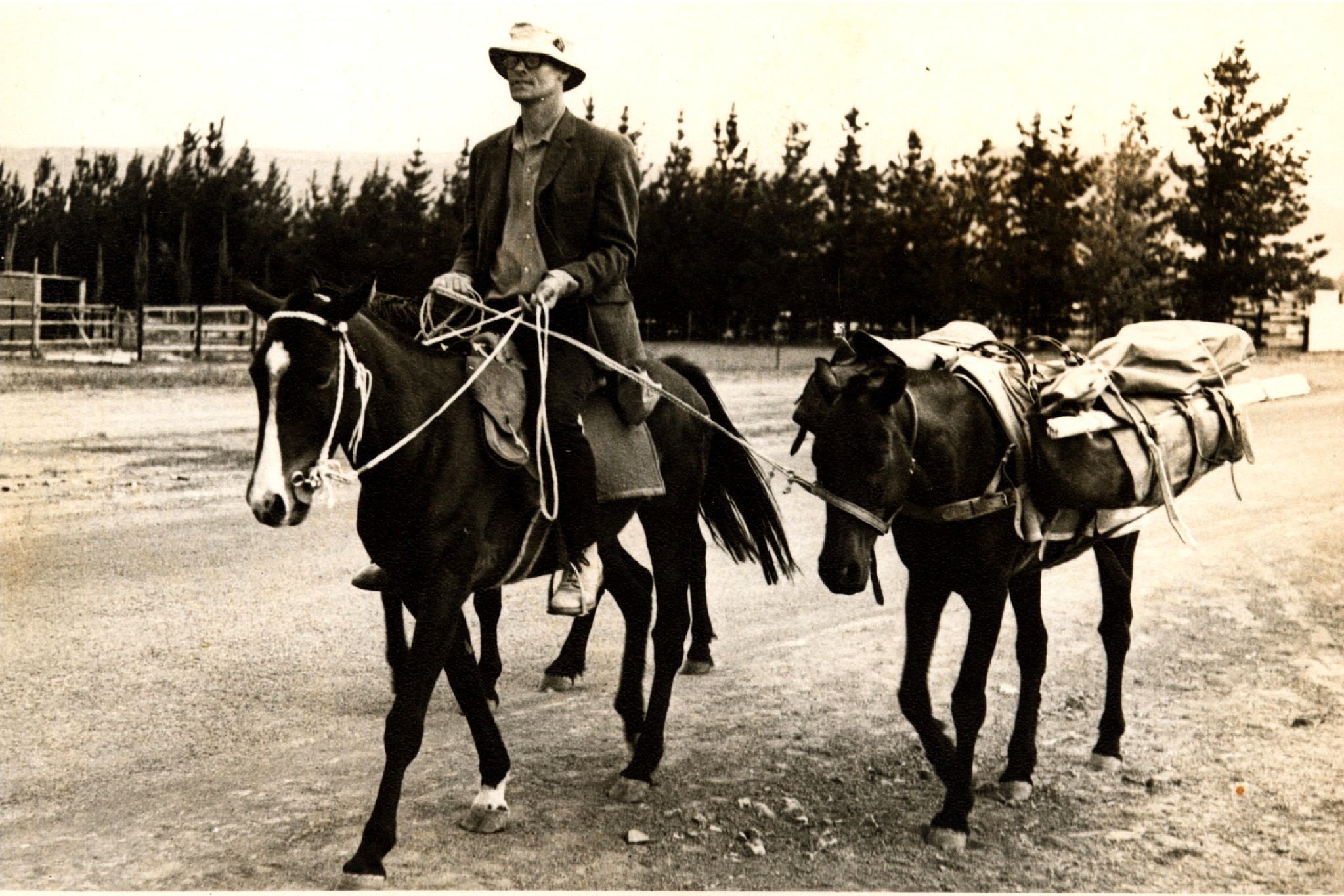

Photo Credits: Dolgan herder and his balok surrounded by reindeer. Photo credit: © Nicolas Mingasson; Dolgan ceremonial boots with bead decoration. Photo credit: Jeff Dyrek, 2002. The frozen ice block containing the remains of the Jarkov Mammoth. Its tusks were reattached during excavation and transport, as insisted upon by the Dolgan elders as a way of paying respect to its spirit and to guard against a potential curse. Photo credit: Jeff Dyrek, 2002. Jeff Dyrek, member of the 2002 and 2003 North Pole expeditions (and proud APS member), in front of the mammoth tusk collection in the Khatanga ice tunnel. Photo credit: Jeff Dyrek, 2002. One of the few mammoth skulls and other bones in the CERPOLEX collection. Photo credit: Jeff Dyrek, Khatanga, 2002. Taymyr Peninsula indicated in red. Cartographer: Hugo Ahlenius, UNEP/GRID-Arendal

![Dolgans&TheirMammoths6[small]](http://www.mikaelstrandberg.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/DolgansTheirMammoths6small2-300x300.jpg)

![Dolgans&TheirMammoths1[small]](http://www.mikaelstrandberg.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/DolgansTheirMammoths1small-300x195.jpg)

![Dolgans&TheirMammoths5[small]](http://www.mikaelstrandberg.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/DolgansTheirMammoths5small-300x214.jpg)

![Dolgans&TheirMammoths4[small]](http://www.mikaelstrandberg.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/DolgansTheirMammoths4small1-300x197.jpg)

![Dolgans&TheirMammoths3[small]](http://www.mikaelstrandberg.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/DolgansTheirMammoths3small-300x215.jpg)

![Dolgans&TheirMammoths2[small]](http://www.mikaelstrandberg.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/DolgansTheirMammoths2small1-214x300.jpg)