Captain Fogel´s life reads like an adventure novel and you need a bit of time to get through his CV of accomplishments. He is an explorer of the old kind, that seems almost extinct today amongst GPS:es and big words. I have gotten to know him just a tiny little bit over the last three weeks, whilst discussing the certain issues within the Explorers Club and he makes me smile all the time. He always seems to be in a good mood and have a whole library full of good stories. So, of course, naturally I begged him to write a story for me and he choose the extra ordinary story about his Expedition down the Omo River in Ethiopia 1973. Enough said from my side, let the story begin!

The Captain’s Log : “The Chief’s Daughter”

By

Captain Joel S. Fogel

“Important events occur in everyone’s life that are the focus of new

directions. These turning points are emotional journeys….they signal

that one way of living is over and a new way is emerging; they are

rites of passage in life.”

Part I — ” The Chief’s Daughter “

It was the Omo River valley in Ethiopia, Africa’s “Hidden Emerald”,

that nearly cost me my life and my sanity.

Do you remember the 1973 fuel shortage, when people stood at the gas

pumps, waiting in anger to fill their tanks ? I suppose it was one of

the first wake-up calls we Americans had regarding our dependance on

foreign oil.

Someone (or a group of someones) had gotten together in Africa and

decided to cut back on the production of that “black gold”. It was the

Organization of African States that had met in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia in

the Fall of that year.

I was there, preparing for an expedition that would change my life

forever. As I ran around looking for supplies and assembling my crew, I

heard rumors of an impending taxi strike in the capital city of Addis.

It always amazes me how things can trigger other things that happen and

you sometimes get caught in the middle. The mystics call it “synergy”

or coincidence. I call it luck.

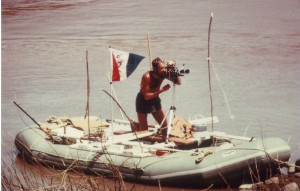

By the time the strike had struck, I had already flown nearly two

thousand miles south into the jungles of Ethiopia along the banks of

the Omo River to begin an exploration by raft for the purpose of

filming the tribesmen who lived in that region.

I was accompanied by an Ethiopian wildlife expert, Otto Tabebu, and an

German anthropologist, Dieter Hanke. The Smithsonian Institute had

indicated interest in an ethnographic film recording the tribal life in

that area and the Walter Reade Army hospital had taken a pint of my

blood for comparison, following my return.

In a sense, I was a human guinea pig. The doctors wanted to sample my

blood again, after I collected specimens of insects for an

entomological survey of disease carrying mosquitoes. River blindness,

malaria, leprosy, and elephantiasis were insect-bourne diseases

reported in the area.

If I contracted something, it would show up in my blood upon analysis

and they would know how to treat it (hopefully).

By the time we had arrived in Mui, the game preserve which bordered the

crocodile-infested, wide, muddy waters known as the Omo River, the

events which would cause Ethiopia’s “Little Giant”, Emperor Halle

Selassie, to be placed under house arrest (after he instigated the oil

embargo which would ironically precipitate his downfall) it was

something we only heard about as we sat around the fire the night

before our historic journey.

We were about to explore a portion of the Omo River Valley for the

first time. It was the upper part of the Great Rift Gorge where famed

anthropologist, Dr. Louis Leakey, had discovered the one

million-year-old “Australopithicus”, the earliest remains of human

kind, several years before our expedition.

The morning of our journey, I woke up to the deep, throaty far-off roar

of a lion. The dry dessert and thorny thickets surrounded us as we

assembled our rowing platform which would sit inside of our 25-foot

rubber raft.

White crates and boxes of food and equipment were scattered near where

the bush plane had dropped us at a make-shift air strip near the river.

The sandy river banks rose thirty feet above the swirling waters of

this ancient waterway, giving it the appearance of a buzz saw cutting

through the desert.

At 29 years old, I was the old man of the group. Tabebu was in his

mid-twenties and Dieter was only 21 years old.

“We must be careful, ” the quiet-spoken Tabebu nearly whispered as we

put the finishing touches on the raft and loaded the gear. “Some of the

crocodiles are as large as the boat and they can turn it over”.

As if to punctuate his comment, a loud slap on the water across the

river, indicated that a huge reptile had just belly-flopped off the

river bank, sliding into the fast-flowing river below.

Mixed emotions accompanied this voyage: there was the anticipation of

the adventure. Fear was a part of the atmosphere as well since we had

heard about warring tribesmen further downstream, and then there was

all of the drama which had led up to our trip on the Omo River.

Originally, I had been part of another expedition led by famed

explorer, Richard Bangs of SOBEK (“The River Gods” and “Riding the

Dragon’s Back” details our explorations of the Omo and the Yangtze

Rivers). We were a group of nearly 20 men and women who had planned to

explore the Omo together.

But tragedy struck: on a preliminary exploration of the Baro River

which flows into the Nile, his rafts were overturned on a waterfall and

one of my friends, Angus McLeod, was drown and lost in the river. I had

broken from the group and set up my own expedition on the Omo.

Now, as we drifted downstream, baking under the equatorial sun, the

sorrow was still fresh although the events were months old.

Gramps used to say, “Joel, never judge an Indian until you’re walked a

mile in his moccasins”.

It’s easy to judge. It’s not always easy to accept.

Here we were in the middle of no-man’s land, collecting insects (and

getting bitten), stopping along the banks to visit small

hunter-gatherer villages of 8-10 people, taking photos and shooting 16

mm film. We traded goods for artifacts which we later donated to the

Smithsonian Museum of African Art.

There were four tribal groups: the Karo, the Bume, the Mursi and the

Nidi. All lived naked semi-nomadic lives along the river banks,

traveling inland during the rainy season to tend herds of cattle that

grazed further back, away from the river.

During the dry season, they would return to the Omo River to fish,

raise millet, hunt wilde beast and gather fruits and plants along the

river. It was an idyllic life except for one thing: the tribesmen

fought each other for the land beside the river to cultivate their

crops.

There were regular raiding parties, as we learned, when the tribesmen

would travel across the river, kill members of the other tribes and

even take some of their women as captives and slaves.

During the course of our expedition, I lived with one of these tribes,

the Mursi, following my contraction of vivax malaria. I had been bitten

by a species of Anophiles mosquito which had not heard about the

propholectic medicine known as “chloroquin phosphate” which was suppose

to protect me.

Now as I lay covered with clothes and a blanket, bathed in my own

sweat, hallucinating between bouts of high fever and chills from the

malaria, the two other expedition members determined that they must

leave me in the care of the Mursi. They would cross the river into the

Sudan, hiking to a Swedish Mission which the tribesmen had told them

was a week’s walk away to the west.

I was in misery for over a week, tossing and turning every 48 hours as

waves of nausea and pain racked my body, causing me to lose weight from

dehydration and lack of food. When I came out of it, I was 10 pounds

lighter, but it was not a diet I would recommend for weight loss.

I remember sitting on the riverbank, pointing to objects which were

familiar as Gaddi, a young tribesman who took pity on me, would

pronouce their name. In this way, I was able to form a crude phonetic

vocabulary which helped me to communicate.

One day, I looked at Gaddi and nearly gave him a heart attack when I

put some of my words together to form a phrase and spit it all out at

once: “Keen art te ? Nabasa art te ?” — “Who are you and where are

you going ?”

His large wide grin exposing beautiful white teeth, broke into laughter

as he realized that I could speak his language. I saw a new sign of

respect in his eyes, similar to what I had witnessed living among other

cultures when I learned to communicate in their “tongues” whichthe

tribesmen called language.

It was about this time, several weeks after my recovery, that the chief

of the tribe, Carante Dahoe, invited me to join him in a hunt on the

plains surrounding the village. We were a group of 5 men that morning

as we gathered to face the rising sun. Gun-blued mountains rose in the

distance as we walked through the mist towards them holding our spears

and leather whip shields.

I climbed a bare-limbed Beobob tree and saw a wart hog grazing in the

distance beside some wilde beast. The group fanned out, staying up-wind

and slowly surrounded the wild pig, gradually closing in on him.

We were successful that morning and my spear was the one that stopped

the boar which carried everyone’s spear in it’s back. As a guest, I

was proud to be able to contribute food to these people since a drought

had begun to affect their crops and starvation was beginning to set in

among the river tribes.

We had fed many people with our supplies during the course of the trip.

But eventually, we had run out. Now, waiting for the return of my

expedition members, I depended on what we could catch for food.

It was a scary time, but also very tranquil and beautiful, watching the

sun setting over the plains as the dust rose from herds of elephants

roaming in the distance. Strange…but I was beginning to feel at home

as though I had once before lived in this place.

My home in New Jersey was beginning to seem a long way from where I was

at the moment. As for that matter, I had no idea where my partners were

either. I found out later about their odyssey across the desert, their

attempts to return for me and the difficulities they encountered in the

Sudan with the officials at the border.

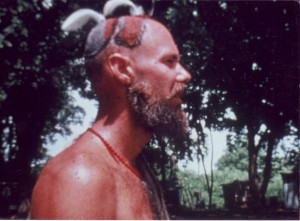

All of that would come later, for the moment, however, I was seated on

a stool by the riverbank as Carante Dahoe and the rest of the tribe

began my initiation into the Mursi tribe through the shaving of my head

and the placing of mud and clay in my hair.

I recall sitting on that stool for nearly six hours, a rite of passage

to test my will and strength as they wove a piece of bone into my scalp

to make the headdress that would officially make me a tribesmen.

When they were done, they painted the clay cap with blood and water,

giving it a red color. And then they named me “Nogolull”, which

translated to mean “the man who came by water”.

I was given a pair of wart hog sandals, a cloth made from the bark of a

tree which was casually worn over the shoulder and a hut that was built

for me by the tribesmen. It was after all of this, several days later,

that the chief presented me with his 14-year old daughter for a bride.

I explained that I was already married with a child and that my wife in

another place was seven months pregnant with another child. This seemed

to please Dahoe and his son, Gaddi. It was proof of my virility in a

tribe where each man had several wives.

I came to understand that this system of polygamy evolved as a result

of tribal warfare where there were many man killed and many women

without husbands. I also learned that their life expectancy was about

25-30 years, a woman had her first child by 14 years old and 50 percent

of the infants died during, or shortly after child birth.

It was a harsh land.

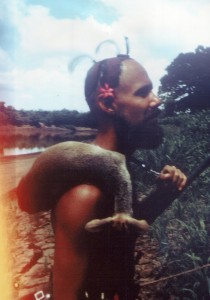

From the onset, I made it very clear to the chief that although I would

accept his daughter, Kafo, as a bride, she would only be allowed to

come to my hut during the day to help prepare the meals. I could not

take on the responsibility of a new family since I was planning some

day to return to my home in another place.

Kafo had been captured by Dahoe in a raid on the Bume tribe many years

before, several miles downstream. She had all of the markings of a Bume

women, including the scars on her shoulders and a large plate in her

lip which was a sign of beauty.

She wore a gazelle skin skirt with pieces of bone in the hem which made

a light clicking sound when she walked from hut to hut, gathering the

fixings for our meals. Apart from that, she was naked. We all were. It

was hot and that was the way we dressed.

I also learned that the mutilation experienced by the men and women of

the tribe was started during the slave trade period, centuries before,

when the tribesmen learned that if they cut and scarred their bodies,

they would be ugly to the slave traders, their value would be decreased

and they would be left alone with their families. Today, they regard it

as a sign of beauty.

That was something else my travels taught me: that beauty was a

relative thing and definitely in the “eyes of the beholder”. The

tribesmen would chortle with laughter, holding their bellies when I

showed them a fashion magazine displaying Caucasian women, fully

clothed and made up with lipstick, eye shadow and nail polish.

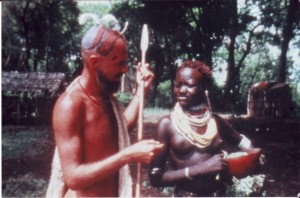

All of this was academic as I stood nearly naked on the Ethiopian

plains beside the Omo River one late afternoon. A small, twin engine

plane had flown low along the river, wing dipping as it passed our

village.

Everyone ran out to the river bank and stared at this great white bird

as it circled the plains, looking for a place to land.

When the pilot arrived, walking towards the village with a member of

the Swedish Mission beside him, their mouths seemed to drop open at the

sight which met his eyes: I was standing beside Kafo in her gazelle

skin skirt, my body, covered with rancid butter the tribesmen used to

keep insects from biting.

My skin was dark brown from the intense sun, a guinea fowl headdress

sprung forth from my forehead. I wore wart hog sandals, a bark cloth

over my shoulder and a spear and leather shield were in my left hand as

my right hand gently draped Kafo’s shoulder.

“Fogel ?” the bush pilot stammered. “Is that you….Joel Fogel ?“

He didn’t seem too sure and hearing my name pronounced for the first

time in English for such a long time….it took me several moments to

respond with a nod.

” Your friends are waiting for you in Addis. There’s been a terrible

revolution and the communist junta has replaced the government. Sorry

to take so long. Your friends were detained but everything is O.K. now.”

But anyone who knew me during that period in my life will tell you that

everything was not “O.K.” I returned from that jungle a changed man.

A terrible drought struck the Sahil Desert within a year after my

departure. Water holes dried up and million died, including many of my

adopted family by the Omo.

I wandered through the U.N. and Unicef, trying to gain the attention of

those organizations, pleading for the children I had seen beginning to

die. I lectured throughout the country about the same topic. But the

world had it’s attention turned towards oil and the lack of it.

I needed to wait for more than 12 years until 1986, when some of the

film I had shot was combined with a BBC film report on the drought

which had killed millions in Ethiopia. “Band Aid” was born and aid

began to flow into the country. But then came Somolia, the war lords

and all of the trouble the world community had getting food to the

starving in Africa.

Joel S. Fogel has been head of the Environmental Affairs for the Philadelphia Chapter of The Explorers Club for the past 10 years. He also is President of the Waterwatch International and sits on the advisory council of the Atlantic County Utilities Authority’s Groundwater Advisory Committee. This year, Captain Fogel was nominated by ACUA for the CNN Hero of the Year Award for his clean water projects around the globe. The South Jersey native was also nominated this year for The Lowell Thomas Award for humanitarian work in Ethiopia during an anthropological expedition in 1973. His other awards include two Presidential Commendations for environmental work and a Carnegie Hero Award nomination for the rescue of a young woman in 1986 when her car went into the bay on Christmas Eve. Visit his home page here!

Thanks, Mikael….this is the first time this article was published. Hope that you enjoyed reading my story.

VTY,

Capt. Joel S. Fogel

Your friend in Exploration !