Ethical Exploration

by

CuChullaine O’Reilly FRGS

There have been a number of entries on Mikael’s blog recently which, though apparently unrelated, do in fact share a common thread – namely the theme of ethical exploration.

Mikael first released a very important article which examined the topic of “Fakes and Cheats.” Though the focus was on polar liars, the topic could have just as easily have been laid at the door of any type of exploration. Equestrian exploration and long distance travel, for example, has its share of frauds lurking in the closet.

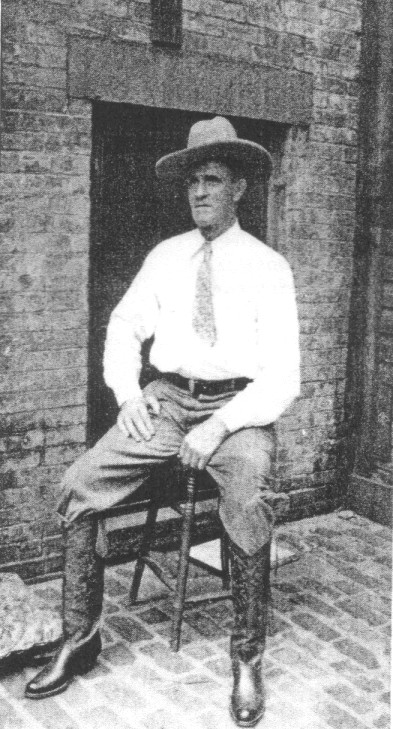

The most notorious of these charlatans was the Old West impostor, Frank Hopkins. Though the fantasies which make up the Hopkins Hoax are too numerous to list here, his most ridiculous mounted deception involved the fanciful claim that he made a lightning-fast winter time ride from Germany to Mongolia, a journey which the ice-delivery man could not have undertaken as he was in fact living in New Jersey with his wife and four children. Hopkins abandoned his family at the depth of the Great Depression, absconding with a young neighbour woman, and spent the rest of his days lurking on New York’s Long Island. From there he peddled wild stories to an American press already addicted to lurid tales involving off-beat countries and phoney claims of resounding bravery.

Hopkins might have been a pathetic footnote to equestrian travel history, if the Walt Disney studio had not decided to release the movie, “Hidalgo,” which they perpetrated as having been based on Hopkins’ “true story.” In reality, the man couldn’t spell “truth”.

Hopkins lied, not by accident, nor to appease sponsors, but to fuel his maniacal desire to aggrandize himself at the expense of authentic heroes. Yet anyone who follows the exploration news released by ExWeb will have seen far too many current examples of people who have sold their souls in order to attain fame and fortune. For example, recently there was a well documented case involving a fraudulent mountain-climbing claim. As Mikael rightly noted in one of his introspective articles, people do make genuine mistakes, in which case, as our host suggests, they should apologize.

But what if it wasn’t a mistake? What if the so-called explorer was, like Hopkins, throwing out the rules, riding rough shod over the truth, chasing a buck, prostituting their personal integrity in exchange for a quick roll in the hay with that whore “fame”?

As Mikael’s sleepless night recently demonstrated, it’s easy to announce that you’re an explorer, yet how do you pay the bills without selling your soul? In an age of electronic media, instant news and the cancerous onslaught of reality-based television, how do individuals maintain their personal integrity in the face of a world who is willing, nay even eager, to wink at exploration exploitation? How can the public trust the media which aggrandises a liar like Hopkins?

The answer, if I may suggest it, is always a personal one. It is a concept which goes by various names, including ethics, morality, principles, standards, ideals. Few men offer us a more dignified example of those rosy words than the Antarctic explorer, Frank Wild.

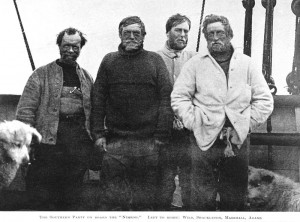

Born in Yorkshire, Wild is one those quiet heroes of Antarctic exploration whom we would do well to remember in this day of exploration chicanery. In 1901 this modest man accompanied Captain Robert Scott to Antarctica on the Discovery expedition. In 1908 he travelled with Sir Ernest Shackleton when that champion nearly bagged the South Pole. In 1911 Douglas Mawson placed Wild in charge of his Antarctic base camp. Between 1914 and 1916 Wild barely managed to survive the horrific series of accidents that crippled the Trans-Antarctic Expedition. This included being marooned on Elephant Island, where he survived on a diet of penguins and seaweed. Finally, in 1921 Wild returned to Antarctica for the last time. During that journey Sir Ernest died of a heart attack, yet his loyal lieutenant assumed command and completed the expedition.

Because he was a genuine hero of exploration, Wild was awarded the Polar Medal with four bars by the British government. The Royal Geographical Society awarded him their Patron’s Medal. The diminutive explorer was made a Freeman of the city of London and honoured with a CBE by Britain’s monarch. Cape Wild on Elephant Island and Mount Wild in Antarctica both bear his name.So, I ask you then to ponder how cruel was Wild’s ultimate fate, as before he died in 1939, virtually penniless and largely forgotten, this brave explorer had been reduced to taking jobs as a storekeeper, cotton farmer, hotel barman, mine manager and railway worker? And what does it say for the true value of the man when I reveal that Wild’s Polar medal recently sold for £132,000 !

What we mustn’t lose sight of, nor encourage to occur, is the base betrayal of exploration’s higher goals. As Frank Wild proves, and Mikael Strandberg recently learned, no matter how many medals a king hangs about your neck, when the fanfare fades you are still left with a host of unpaid bills and a crowd of vindictive enemies who will envy your success and even steal your dog.

One should never be tempted to pawn exploration’s greater glories for a dose of fizzy, transitory, cheap fame. A recent case of exploration exploitation was revealed in Nepal, where a Sherpa announced that he is planning on taking his ten-year-old son to the top of Everest. Why? So that the child can beat the already dubious record set this year, when a 13-year-old California boy became the youngest person to climb that sadly soiled peak. This isn’t the act of a reasonable father. These are the actions of a money-hungry sperm donor.

What are we to make of the startling dichotomy between Wild’s genuine bravery and the Nepalese parent’s aggressive ambition? Why should we care? Because our frail planet is in desperate need of genuine exploration heroes. Allow me to explain.

In the summer of 2008 an area of the Arctic sea ice twice the size of Great Britain disappeared over a couple of weeks. Nor is our globe’s trouble confined to the Poles.

Five hundred miles off the coast of California a rotating oceanic current called the North Pacific Gyro is acting like an oceanic toilet bowl. Lodged within this plastic vortex, which is nearly six times the size of Great Britain, is an estimated 100 million tonnes of man-made waste and debris, including plastic bottles, tyres and chemical sludge.

Of equal worry are two other recently discovered facts. For the first time in the history of our planet, a single species, humanity, has become the dominant ecological force, and scientists predict that fifty per cent of all known species currently inhabiting the Earth will be extinct within the next fifty years.

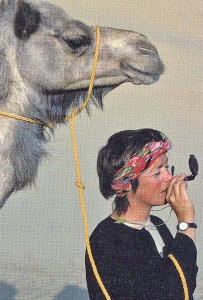

In the face of what appears to be an on-coming climatic catastrophe, why do the wanderings of Arita Baaijens and Mikael Strandberg matter? Who cares if she disappears into the Sahara with her camels or if he ventures back into the frozen wastes of Siberia again? If their journeys don’t make a buck, pull in an audience or promote a product what good are they?

This isn’t a new message. It is the cynical philosophy of transitory greed. It’s the siren song which every explorer confronts, in the dead of the night, when they awake, in a cold sweat and wonder, like Frank Wild, Mikael Strandberg, Arita Baaijens and others have done, why they’ve made such a difficult personal decision. This is the late-night soul-chilling moment when they wonder why they forsook a normal job, a dependable emotional relationship, a pension, in fact all the things that their peers sought, and found, embracing instead the explorer’s constant companions, personal confusion, emotional despair and financial loneliness.

As Wild proves, you don’t become an explorer because of the pay. That’s why in this day of celebrity authors, lying politicians, venial television stars and common day crooks, the handful of true explorers shine like bright stars in a world full of transitory mediocrities.

Ethical exploration has always been one of humanity’s sterling accomplishments, because lodged within that tiny cadre have always been a handful of men and women, like Mikael and Arita, who throughout the long march of our species, have summoned the courage to march away from the safety and taboos of their hereditary village, and set off into the unknown in search of scientific and personal knowledge.

Our species will always need ethical explorers who continue to seek the outer edges of knowledge. As Frank Wild proves, television can’t make you a hero of exploration. Only your own rock hard grip on personal ethical behaviour will steer you through the shoals of deceit and onto the shore of true spiritual bravery.

CuChullaine O’Reilly is the Founder of the Long Riders’ Guild, the world’s international association of equestrian explorers and a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society and the Explorers’ Club. He is currently completing the “Horse Travel Handbook,” the most comprehensive equestrian exploration guide ever written. This is his second article as a guest writer. Read his first here!

A very thoughtful post. I agree with many of your points. I think the community of explorers, in many respects, mirrors the broader human community. There are some who are motivated by principle, others who are motivated by fame or self-aggrandizement. Most I suspect are somewhere in the middle, influenced by principle and self-interest (just like the rest of us!). I don’t agree though that “Ethical exploration has always been one of humanity’s sterling accomplishments.” To the contrary, most expeditions into the unknown had very specific commercial, political, or military motives. Even those expeditions that “set off into the unknown in search of scientific knowledge” e.g the voyages of James Cook, the Western Surveys, or NASA’s Apollo program, had, I would argue, political motives that were stronger than the scientific ones. As for those of us who travel and explore for “personal meaning” need to look critically at their own motives. The George Mallorys and Chris McCandlesses of the world have great passion and drive, but their motives are usually far more complex than then make them out to be.

Dear Michael Robinson,

Forgive my muddled writing, as if I had thought to explain myself properly, you would not have raised a noteworthy criticism of the opinion piece.

You wrote, “I don’t agree though that ‘Ethical exploration has always been one of humanity’s sterling accomplishments.’ To the contrary, most expeditions into the unknown had very specific commercial, political, or military motives. Even those expeditions that set off into the unknown in search of scientific knowledge’ e.g the voyages of James Cook, the Western Surveys, or NASA’s Apollo program, had, I would argue, political motives that were stronger than the scientific ones.”

The examples you provided, i.e. NASA, Cook, etc., certainly reflect documented national efforts to expand mankind’s general knowledge, all the while enriching the host nation and all too often the individual explorer as well. Christopher Columbus certainly springs to my mind, when I contemplate the idea of pushing into the unknown, armed with a flag, a religion and an empty pocket book. Thus, you were right to point out that history is replete with similar examples.

Yet, because of my work with the Long Riders’ Guild, when I penned the article I was quietly focusing in my mind on the individual efforts of equestrian explorers, who nearly always either travel alone or in twos. Unlike current expeditions to the Everest summit, with their caravans of sherpas, mountains of gear, hefty budgets, etc., Long Riders are largely independent, self contained and solitary. They also represent that critical point which I forgot to mention in my article, namely the vital role of the “citizen explorer,” as opposed to the nationally endorsed or commercially sponsored “super” expedition which you rightly brought to our attention.

In contrast to the national expeditions, throughout history Long Riders have set off to ostensibly reach a distant geographic point, all the while many of them are busy internalizing and contemplating a wide variety of thoughts, possibilities and impressions. It is this profound “silence of the saddle,” which featured so prominently in the lives of Charles Darwin and Jonathan Swift, both of whom were enthusiastic Historical Long Riders whose equestrian journeys provided a spark for their later famous literary works, i.e. Swift wrote “Gulliver’s Travels,” with its famous talking horses, after having ridden his beloved mare across Ireland, and Darwin happily explored three continents on horseback, every time the Beagle gave him an opportunity to go ashore.

Yet, just like the main-stream exploration world, modern Long Riders have given us both remarkable heroes, who epitomize the concept of the citizen explorer, as well as mounted knaves, who have ruthlessly exploited the public’s trust.

The Australian Long Rider, Tim Cope, epitomizes the former, in that his recent 6,000 mile solo journey from Mongolia to Hungary, was not only a modern “first,” it also resulted in Tim documenting the tremendous cultural impact which mounted nomad culture continues to exert on the world. Here is a link to Tim’s noteworthy and noble expedition.

http://www.thelongridersguild.com/cope.htm#new

Sadly, at the same time Tim was riding in the hoofprints of Genghis Khan, the Guild became aware of the most ruthless case of equestrian travel exploitation in modern history. The knave involved in this case was caught by a reporter who had been tipped off to the fact that though the fellow claimed to be riding from Mexico to Canada, he was in fact comfortably living in his girl friend’s house in Las Vegas. The reporter observed the con man standing on the front lawn, talking on his cell phone in Las Vegas, while pretending to be sitting next to a campfire in Wyoming. What’s worse, this fellow had defrauded numerous private businesses, fraudulently claimed he was supported by the Roy Rogers orphanage, and even misused the “Cowboys for Christ” organization, all the while he was busy collecting funds for a phony children’s charity. Here is a link to the notorious case.

http://www.thelongridersguild.com/knave1.htm

After Mikael published my opinion piece, a trusted travelling comrade from Sweden, Hadji Abdul Haq, shared his thoughts on the need to emphasize ethics in exploration.

“There is plenty of material here for thought, for anyone venturing on the exploring track. As this article points out, to be an ethical explorer is not for the faint of heart. An explorer needs to have guidelines for right and wrong. Not only do they make it possible for the explorer to judge himself and his actions against a constant ethical barometer, it also reassures the public that the explorer’s actions are not based on what he thinks is the best for himself at any given moment,” the Muslim philosopher said.

As my article pointed out, regardless if you are riding across Mongolia or walking to the North Pole, everyone of us who shares our personal dreams, and professional ambitions, with the public has created a de facto agreement wherein we present ourselves as being trustworthy. Moreover, regardless if the cheater is exposed for having falsely claimed to have climbed Mt. McKinley, to have lied about racing across Australia or caught riding across America fraudulently disguised as a Christian cowboy, the end result is that the public’s trust is always eroded and the noble enterprise of exploration is soiled.

Trust, not money, and regardless of any flag, needs to be the foundation on which modern exploration is based.

Kind regards,

CuChullaine

Thanks for following up CuChullaine. Yes, I can see how the context of story changes things. I do not know much about the Long Riders Guild, but I can see how they frame the arguments you make here. My research in exploration has made me a bit jaded about motivations since I often see such a disconnect between public pronouncements and private actions. Moreover, the expeditions that I have looked at most closely — polar expeditions — often had very big stakes (e.g. wealth, prestige, celebrity) that make it difficult for explorers to disentangle their own motives. But I need to be careful not to interpret all expeditions according to this single framework. I see this more clearly now that I have begun to branch out into other arenas of travel and exploration:

http://timetoeatthedogs.com/2009/01/29/maybe-i-was-wrong/

Good luck in you work!

Michael

The skeptic ‘sound’ of Michael Robinson’s comment as to the ‘real’ motives of the adventurer/explorer is lacking in my view a true understanding of the unmistakable effect of the sailing away from the safe harbor.

Whatever were the initial motives that drove one to sail away from the safe harbor and venture into the unknown chances are that the effect of the initial motives will not last long but rather be replaced by new motives and new horizons that one could never foresee before.

One should only make his way into the freezing brutal ice field of Siberia or wave goodbye to a small cheering crowd on the shore and row into the unforgiving horizon to find out if those initial ‘safe shore’ motives (i.e., Robinson’s ‘fame’ or ‘self-aggrandizement’) really ‘hold water’ or else ( see for example – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vLJSQ0XbfUA&feature=player_embedded ).The growing weakness of these arguably driving motives is especially evident when one chose to make the daring voyage alone, with no one to rely on, when no one can even see him or her in their misery and extreme depravation state. When no one could give a hand. When there is not even a single person to witness what could turn to be his or her last moments.

As a matter of fact one can make the argument that those who cheat as to their journey are actually the one who could not bear the inevitable loss of their initial motives and by that deprive themselves from what could be their greatest discovery of all. As Roz Savage put it in her usual wonderful way (during her row across the Atlantic ocean): “It doesn’t matter the person I was at the start of the race,” she said,“She doesn’t exist anymore. What matters is the person I’m now. The lessons I have learn along the way and that I’m putting it into practice.” The new motives or horizons that are waiting to be discovered are far greater than fame or alike, The illuminating personal effect that comes with the desire to push the known or ‘forced’ boundaries and go further beyond is much precious than the cause of doing so for the sake of scientific or geographical discoveries or for political or military reasons. It is rooted in the living quest for breaking out of the darkness and the growing sense of freedom, illumination and eventually happiness that such ventures brought and bring to the true doer.

I think that one of the reasons that adventurers find it hard to adjust when they return to the shore is because they find that their inner values and perspective had changed quite a bit and they feel confused by the contradiction between what they experienced and learnt and what the culture of the ‘safe harbor’ regards as important, sound or safe. The contradiction between a society that value order, stability and the reduction of chaos vis a vis the adventurer’s realization of the beauty of Nietzsche’s insight that “one must still have chaos in oneself in order to give birth to a dancing star.”

The contradiction between a culture that was pushed and forced to think that achieving security is what life is all about vis a vis the adventurer’s realization that as Helen Keller wonderfully put it that “Security is mostly a superstition. It does not exist in nature, nor do the children of men as a whole experience it. Avoiding danger is no safer in the long run than outright exposure. Life is either a daring adventure, or nothing.”

The group of the true adventurers might be very tiny in size but its importance to and impact on humanity is nothing short than priceless. They carry the most ancient flame of the human spirit and remind us that personal freedom is not just a slogan or mere empty words. It is something that is within our reach if we only let ourselves the chance to truly Explore. Dream and yes Discover.

I once read that a physician name Dr. MacDougall placed dying patients upon a scale in order to measure the weight of the human soul. MacDougal postulated the soul was material and therefore had mass, ergo a measurable drop in the weight of the deceased would be noted at the moment this essence parted ways with the physical remains. He found that the human soul weights just 21 grams. Now what is a body, no matter its weight, without this 21 grams? Nothing. What are we and where would we be without this tiny group of truly dancing stars?

JR: I agree with you that many explorers and adventures seek to “break out of the darkness” in search of a “growing sense of freedom, illumination and happiness.” Certainly these things motivated me on my travels to the Arctic, the Middle East, and other places. And at moments — usually when I was most alone or most in danger — I felt the world peel away and something profound emerge. These were searing experiences for me and I will never forget them. Despite my skepticism about motives, then, I believe that extreme experience has the power to change people, lead to deep insights, and altered states of being. (I write about this here: http://timetoeatthedogs.com/2009/08/05/blue-hole/)

Yet even if high adventure leads to moments of self-discovery it does not follow that high adventure is ethical or that its “impact on humanity is nothing short than priceless.” Exploration, after all, involves moral decisions of greater weight than pursuing freedom, finding enlightenment, or escaping civilization. It has consequences for those left behind — spouses, children, parents — as well as those who are charged with rescuing adventurers in trouble — helicopter pilots, sherpas, Inuit guides, and Coast Guard crews.

I wonder: is the ‘culture of safe harbors’ as you put it, is really a world devoid of challenges and dangers? Or is it that the challenges are simply more complex? After all, the risks of climbing an 8000 meter peak are daunting, but knowable. The expedition has a beginning, a dangerous climax, and an end. By comparison the world back home is more messy, open ended, more difficult to assess. Where does one find the inner chaos that makes one dance between reason and madness? Ascending the Eiger? Or staying up all night with a crying child?

Michael,

You are on the right track. Keep going.

D

Hi Mikael,

I’ve been diving into your blog posts with the little free time I have

left these days. The long debates about the ethics of exploration, and

even the definition of exploration has floored me. I know I’m a rookie

in the world of adventures, and completely naïve to the reality of

long expeditions. I have to say, I’ve never given much thought to

defining myself. I’m just going on a bike trip and mountain trek, and

the reason I chose to publicize the event was to help with the

fundraising for the children’s centre.

When writing press releases, creating my blog heading, and doing

interviews, I loosely tossed around the terms I read in the writings

of explorers and other cyclists. Maybe I figured everyone would

understand that this trip has always been simply ‘because I want to do

it’. My experience in Peace Corps has taught me that it would be a

wasted opportunity to do something like this and not try to raise

money with it. So, I came up with an expedition name, even designed a

logo, proposed the idea to my favorite charity and town, and wrapped

it all in a nice PR package for internet consumption. It looks like

the plan is working, as I’ve already raised 300 British Pounds without

cycling one meter. I have to say though, that I’m doing all the leg

work now so that the fundraiser is on autopilot after I start. I don’t

want to think or worry about the money coming in while I’m actually

out on the road.

In a very roundabout way, what I’m trying to express here is two

things: I’m doing this trip because I want to, and I’m learning the

importance of full-transparency in what I do. I’m going to start off

from Lake Assal on a bike. Right now, that’s all I can say with

absolute certainty. Anything that changes along the way is part of the

trip. I’ll improvise as I go, because hey, this is Africa. If I ever

make forward progress using a means beyond my own power, I’ll admit

it. If I detour from my route, I’ll explain why.

People have asked me if this has been done before (traveling from the

lowest point on Africa to the highest, by human power), and I don’t

really know. I think Riaan Manser might qualify. To me, it never

mattered if anyone did it before me. I still want to do it, and

experience it for myself. I’m going solo because no one that I invited

wanted to come along. However, people are really talking me up. They

think that I’m the most noble person in the world, or the biggest

badass. I feel that neither are true. I’m just Kyle, and I’m going for

a bike ride.

I don’t want the praise to go to my head. I’m a generally humble

person, and Ethiopia has enhanced that trait in me. I don’t want to

fall into the stereotype of being the amateur man in his mid-twenties

that thinks he can conquer a mountain, or be faster than the next guy.

Thank you for putting these thoughts out there. It seems that you have

taken some professional and personal attacks as a result, but this was

obviously something people had strong feelings about.

I’m just as flawed as anyone else, but with only a few weeks before I

start a trip that has become bigger than I ever imagined, I’m going to

keep the points stressed by you and your readers in my head. Hopefully

I’ll succeed in reaching the top of Kilimanjaro, but more importantly,

I hope I reach it with integrity.

You’re an inspiration! Thanks for creating a website that’s about more

than your own personal achievements. It’s good character that makes

heroes. I’m still at a point where I’m defining my own values in life,

so a little guidance goes a long way for me.

Kyle Henning

Just saw this link at http://www.adventure-journal.com/2012/10/the-list-the-9-biggest-adventure-hoaxes/