I first came across this extra ordinary fellow called David Renwick Grant back in 1996 when I was planning my Patagonian trip on horseback, he gave me a book about his amazing journey with his family and he taught me a lot. Most of all he inspired me a lot! He still does. We have been in contact on and off throughout the years, lately on Facebook, where he is one of the most dignified of my 2137 friends. Not long ago I read about a Family on Bikes on Facebook and felt a lot of joy! But when reading about them I realized they were very criticized by people who thought it was crazy to bring children travelling. I was stunned! We have only been sedentary, we humans, for no more than maybe a 1000 years of our total of 150 000 as a species. How than can travelling be bad? So I asked David Renwick Grant what he thought.

THREADS FROM THE TAPESTRY

by

David Renwick Grant

I was on board the RSS Discovery last week. She’s berthed permanently in her home port of Dundee, where she was built and it was several years since I had had a look at her. Whatever their preferred means of travel, I would defy anyone who walks aboard and looks up at the crow’s nest not to see in their minds eye a landscape of ice and snow, instead of the solid stone face of Dundee and the gently-flowing river Tay. The old ship has been much modified over the years but you can still stand at the wheel or look into the galley or view the restored cabins of Scott and others. I could feel a tingle start in my feet, as I contemplated faraway places….

Scott’s two expeditions were massive affairs, as was Shackleton’s and to a lesser extent Amundsen’s. At the other end of the world, Nansen’s voyage in the Fram was equally large. Yet, I reflected, it is not essential to be equipped as if for a military operation. Nor is it a prerequisite to have spent years in training and be hugely fit. Had it been, my family and I would probably never have started, let alone completed, the first, and so far as I know, so far the only global circumnavigation by horse-drawn caravan. Yes, I did write ‘my family and I.’ Horse travel is slow, it’s a long way around the world and I wasn’t going to leave them behind for years. Seven years, as it turned out.

The idea of travelling en famille had begun almost as a joke, during a particularly vile day of low, scudding cloud and horizontal rain, sitting by a fire that would not draw and with smoke blowing back down the chimney into the room. The carpet was partially airborne but not from magic, just the draught blasting in under the door. The three children were pretty small then, which ruled out walking and cycling, I never learnt to sail and anyway (ex-)wife Kate got seasick. So that seemed to leave converting a bus, truck, or retired fire-engine perhaps. Anyway, we did nothing about it then, nor in the following year but we talked about it more and more often. Then one day, while I was working away from home, living in ‘digs’ (lodgings) in Lancaster during the week, I was lying in bed reading a magazine. I turned a page and there was this article about horse-drawn caravan holidays in Ireland and a most beguiling picture of a skewbald cob pulling a light bow-top wagon. That was it! That was how we should travel. And, about two years later, we did.

The process of preparation we went through is largely common to any extended journey. In addition we had to find a suitable caravan and suitable horse. It would have been good to have found some suitable sponsors too, but 560-odd letters produced only a limited amount, nearly all donations or discounts, for which we were very grateful but which was never going to be enough. The caravan ended up being purpose-built, to my own design, by Gaulds of Crieff, Perthshire. I had been advised that the Netherlands was the best place to seek a driving horse. This would also avoid the need for the extensive palaver involved when crossing a frontier with a horse – and risking life, horse and caravan to manic motorists on Britain’s narrow roads. There was a very steep learning curve to follow, though, before we finally set off, nearly five weeks after crossing the North Sea.

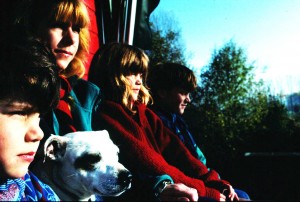

You learn a lot about people when you travel during a seemingly continuously wet autumn, through the monotonously flat beet-growing countryside of northern France. The caravan seemed to get smaller and smaller as it filled with more and more wet gear and we were confined to sitting in it, at day’s end, because there was nowhere to go and more wet walking held no appeal. In fact, the children, who were only ten, nine and six then, stayed aboard most of the time and if it was flat enough, I would ride on occasionally, though it was actually warmer walking. With little to look at, villages few and far between, even I was beginning to wonder whether we were quite daft. The children bore up amazingly. It was as well that we had a good, if limited, supply of books and games with us and many a deadly session of Yahtze, Vulgar Bulgars or Nine Men’s Morris kept everyone amused of an evening when cooped up with rain still hammering on the roof.

The children were fantastic travellers. As we inched our way across the map of Europe, then Central Asia, their capabilities of course increased. Of school there was none but plenty of home education more than filled the gap. Some basics, especially arithmetic and English for Fionn, who had only attended one year of primary, we taught. Most of what they learned was autonomous, though, absorbed almost osmotically. Geography was all around; arithmetic was course and distance calculations and money changing; history was often just chat, if Scottish, or visiting places like Avignon, or Budapest, or Kiev… And as it happens, they did go to school, in Slovenia, by invitation, for two terms, where they were taught in Slovenian!

By the time we had reached the Ukraine, crossed Russia and reached Kazakhstan, we were all seasoned horse-drivers, foragers, wood gatherers and, to an extent, quite good linguists. Our first horse had proved too light and been changed back in France for a solid one-tonne model, who had by now become a much-loved member of the family. The further east we went, the more hospitable and friendly people became. The weather, however, did not and we had a fairly hellish couple of months before finally arriving in Almaty, the then-capital of Kazakhstan, in temperatures of -28° with plenty snow on the ground. The wonderful thing we had found was that, moving along at walking pace meant one could meet and talk – or at least communicate – with people along the way.

We always stopped for winter and that gave us all sorts of opportunities. I have a tape of Eilidh interviewing her little brother for Slovenian radio in Slovenian. Torcuil and I took to the skies in a microlight in Hungary. In Russia, we went trawling for crayfish. We had seen the empty shops of rural Ukraine, Russia and Kazakhstan – and learnt the secret of obtaining supplies in many different ways (all honest, I must add – we never stole so much as a cabbage).

There came problems in plenty, of course. We were hit glancing blows by cars in France and Italy. We were held back, sometimes for days, by the paperwork required for taking a horse across an international border. It took a week to wear down the Russians and get through to Mongolia – but in the interim we were taken to a concert by the Direktor of the Rajon where the noted Kazakh singer Roza Rimbayeva gave a stunning performance and somehow I ended up on stage at the end! We were bothered by drunks on several occasions, the worst of these leading to a serious situation in Mongolia where the prospect of gaol for me loomed, for a while. In fact, the only times I felt threatened were caused by drunken behaviour; even wartime in Yugoslavia seemed safer. Traceur, our ‘main engine’ was largely healthy right up until our last winter, in South Dakota, where, tragically, he died of a brain tumour.

Mostly we had great experiences, a lot of fun, much hard work, saw superb swathes of still-unspoilt parts of the planet and encountered some wonderful people. The children survived our return and have all been doing well in their chosen spheres. I was the one who seemed to find it hardest to settle down. So much so, in fact, that I set off on a solo kayak journey across the Baltic from Sweden, then up and down the rivers Dvina, Ulla, Berezina and Dnepr, finishing on the Black Sea at Odessa. It was different, contained a lot fewer pressures because I had no-one else to worry about, but was not, on the whole, as enjoyable.

What I think we demonstrated very convincingly is that there are ways to travel as a family, even over an extended period, that neither break the bank nor destroy the life-chances of the children involved. Indeed on the latter point, the reverse is true. I mean, how many kids get the chance to jog along on their own pony across the Mongolian plains while reading a text-book! Financially, I reckon it cost us approximately £10,000 per year, which is pretty modest for five people, a horse and, for part of the time, two dogs. £70,000 is still a fair lump of money of course, even today; it came from the proceeds of the sale of our house, plus some fees for writing and even for tuition on a couple of occasions. With hindsight, we should have prepared some sort of act or entertainment we could have offered – a portable means of making money and one that does not require a rigmarole to do.

As John Ridgway wrote to me before we left: “Do it. You’ll regret it for the rest of your lives if you don’t.”

A short biography of David:

At the end of 1997, David Grant – and his family: ex-wife Kate, children Torcuil (1980), Eilidh (1981) and Fionn (1984) – returned from travelling around the world with a horse and caravan, an unique journey which took them seven years; across fifteen countries on three continents and, incidentally, into the Guinness Book of World Records. His story of the family’s epic global journey was published by Simon & Schuster as The Seven Year Hitch, (1999) and in paperback in 2000.

Before this, he had worked as a jackaroo and sheep-shearer in Australia, in ecology and wildlife management for the Nature Conservancy (now Scottish Natural Heritage), as a crofter and prawn creel fisherman on Skye and as part of a film-crew on Orkney.

David was educated in Edinburgh, at George Watson’s College and Merchiston Castle School. After a year in the paper-making industry, he went to Aberdeen University, graduating with an MA degree in 1963. Two years in Australia followed, before a return to university, Edinburgh this time, to take a MSc degree in ecology and wildlife management.

In 2000, David undertook a solo kayak expedition from Sweden to the Black Sea, following an old Viking trade route via the rivers Daugava/Western Dvina, Ulla, Berezina and Dneiper. Along the way, he kept a look out for traces of Vikings, observed the way of life in places he passed and kept a note of the wildlife he saw, and visited local Bahá’í communities. The book about the journey, Spirit of the Vikings, was published in 2007 by The Long Riders’ Guild Press.

David’s other books are: A Submarine at War – the brief life of HMS Trooper (Periscope Publishing, 2006) about the World War II T-class boat in which his half-brother lost his life along with the rest of the crew in 1943 and The Wagon Travel Handbook (The Long Riders’ Guild Press, 2007), a distillation of his and others’ experiences of preparing for life on the, mainly horse-drawn, road in the 21st century.

We enjoyed a wonderful evening with the Grants. They were camped for the night in a field across from our farm just outside Warman, Minnesota. I walked over, introduced myself and invited them for dinner which they graciously accepted. Only yesterday, we were reminiscing about that chance encounter. Fionn lingered behind to shoot a few baskets when the family stopped in to say good-by the next morning. I can’t remember whether he caught up to them by bicycle of if we gave him a ride to meet them. They were not gone long when their wagon tongue broke, they returned and my (ex)husband, Dick LeCocq, welded it for them. David mentioned that the last time it had been welded was in Mongolia and the only material they had to use was barbed wire, if I remember correctly.

It must have been July 1996 when I was driving in the east of Kazakhstan, 90 km south of the closest town and 400km to the cities with an airport with connecting flight to Moscow or Alma-Ata, when I drove past them and then returned in bewilderment. We had a chat, the kids were sitting at the back of the caravan just like on the photo. Couldn’t stop thinking about the Grants since then, thank God, surfing this time was lucky to have found news about them.

I so enjoyed the richness, depth and difference of the journey by the Grants.

And have to ask;

What of the kids? Have they ‘settled’ for what is predictable and sure? or unsettled & off-the-cuff? or a mixture of both?

thanks,

Helen McMullen

Callala Bay, NSW

Australia