Guest writer number 14, Barry Moss, is one of my very best friends. He is pretty much good at everything he puts his heart to. A real human being. I have begged him for ages to write about his ideas about life. Finally, he put his Sunday paper down, jumped the morning bacon and eggs and put pen to paper. Enjoy!

Planes, Volcanoes and Everything.

My name is Barry Moss and I am the Chairman of the British Chapter of the Explorers Club.

My great friend Mikael Strandberg has asked me to write something for his blog.

Having become a slave to my own computer in recent years, I realise that I have unwittingly turned into an addled junkie, trying to read, absorb and digest far too much information. How much of this information will I use? I guess very little of it, but like any drug I am drawn back into its clutches. So, if you are like me, I hope that this short essay will only take up a few minutes of your valuable time and will be interesting enough for you to continue to read to the end of this page at least. I promise that I will not fill you head with too much useless information.

I consider myself fortunate enough to live some days in London and other days in a small mediaeval village complete with castle on the beautiful and wild East Coast of England.

The county of Suffolk is known for its big skies. But what is a big sky? Isn’t the sky huge everywhere? Well, apparently not and I would agree that this part of Suffolk does have big skies, only today the sky was different.

I try to motivate myself when I am here to take a long early morning walk to observe the birds, the hares, the changes in scenery and everything. I was not disappointed this morning but one thing was eerily missing. The all too familiar demented white slashes across a perfect blue canvas had gone. The picture was pristine, the big powder blue sky had been repaired; no aircraft contrails chalked across it. Situated under one of the main east-west air corridors in Northern Europe, I realised that I was looking at a vista that has rarely been seen here since the beginning of the jet age.

I have been on the periphery of aviation industry for most of my life and it remains a technology that still manages to thrill and captivate me. Some days I am fortunate enough to look out of my office window across the river Ore to the secretive Orford Ness with its Mayan like ruins where Britain’s atomic weapons trigger mechanisms were tested in dark, frightening, sinister laboratories. I am at first drawn by the noise, the unmistakable sound of a Merlin aircraft engine. I search above me and to the distance beyond and there it is, a Supermarine Spitfire diving, rolling, dancing across the big blue sky.

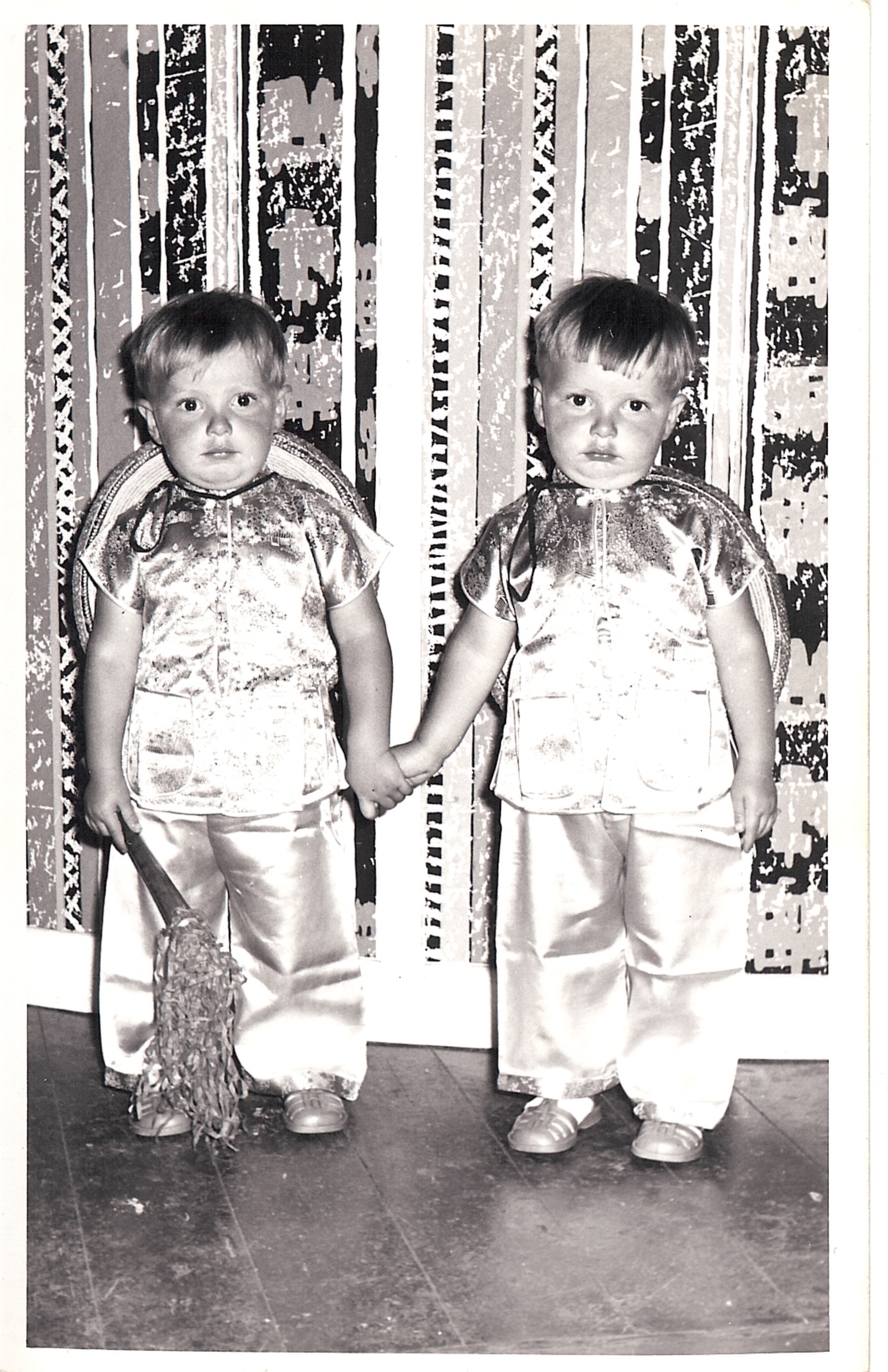

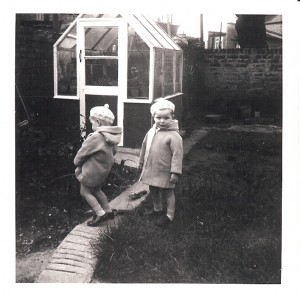

My interest in aviation goes back to when I was a small boy. I vividly recall dreary, depressing and austere Saturdays in East London sitting on a red Routemaster double decker bus. I rarely noticed that the bus ride was often mundane as I would be completely immersed in the picture on the box I had in my hands. One Saturday it could be a Hawker Tempest firing rockets at a line of Panzer tanks the next Saturday on the bus with my father and twin brother it could be a Dassault Mirage III taking on a MiG jet of some type or another in a dog fight.

I was often too eager to bother to follow the Airfix kit assembly instructions, only to find that I had glued the two halves of the fuselage together before inserting the pilot sitting in his ejector seat or the undercarriage nose-gear. The two halves would then be prised apart with a knife or some other blunt instrument which often resulted in the sort of destruction done by metal fatigue test rigs on real aircraft. Corrosive glue would be unwittingly smeared across clear plastic canopies, resulting in disappointment at the irreparable blur that I had caused. Silver paint on wings would have finger marks on it or brush hairs or dust. Transfers applied before the paint had dried. It didn’t really matter too much because the image that these models represented was far greater than my childhood imperfections at assembling and painting them.

My father however was a talented modeller who had the patience, skill and aptitude to build model aircraft out of bits of timber completed with electric motors that turned propellers powered by tardis lookalike batteries. His real passion however was lead soldiers and I am now at the age where I share his frustration that my eyesight is no longer any good for intricate or detailed work, even with spectacles.

Between then and now I have been fortunate enough to have worked with real aircraft manufacturers and have visited super-jumbo passenger aircraft assembly halls that are so large that it is difficult to gain a sense of perspective and scale. I have flown in biplanes and was once fortunate enough to fly a Mig 25 interceptor at three times the speed of sound to the edge of space.

As a child I remember living on the penultimate floor of a block of council flats with my grandparents. Looking over the balcony, the immediate foreground still contained sporadic barren areas of buddleia, smashed cellar caverns and rubble thanks to Adolf Hitler, his Luftwaffe and the Nazi’s secret, terrifying V1 flying bombs and V2 guided missiles. Churchill had employed my grandfather for five years to try to shoot such things down from the rolling deck of a high octane fuel carrying tanker. He reckoned he had hit one or two before the day when a Dornier or something similar dropped a bomb on him before he could take aim. Fortunately for him, although he was wounded, it failed to explode and ignite the tonnes of aviation fuel onboard.

Looking up at the sky from the balcony, my grandfather and I watched the first generation passenger jets on their landing approaches into London Airport. Their deafening four jet engines pierced and crackled and bellowed trails of smoke, in fact similar shades of black, grey and white as the volcanic ash presently spewing into the atmosphere. In those days only the rich and famous flew in jet planes, a fact that didn’t seem to bother us too much then.

Now we all fly. The rich and business people in cocooned sarcophaguses called ‘flatbed’ seats where you may not get a glimpse of the person sitting next to you for 12 hours. That’s unless of course you need to visit the toilet in the dark and you sit there pondering for probably an hour or so how you are going to hoist yourself over your neighbour’s legs without waking him or her up and then doing the same thing in reverse. Having practiced this exercise for many years, I have concluded that even with the skill, training and dexterity of a Chinese child tightrope acrobat it is a manoeuvre that is almost impossible to perfectly execute, particularly in slight turbulence.

Meanwhile Joe public down the back have paid to have an even bigger problem with knees wedged up against seat backs like a created veal calf. Only the super rich, famous and investment bankers have cracked the problem by flying in private jets. However even this indulgence may not be all it seems as many smaller private jets do not have toilets. I have a friend who shall remain nameless who has to live with a major embarrassment for the rest of her life. She had to ask her male colleagues on a tiny private jet to look away whilst she had to do what she had to do in a wine bottle. Imagine walking into the office the next day knowing that everyone knows that’s what you did. Surely you would prefer to have crashed in flames and never be seen again?

As I write this a 1960’s vintage Jet Provost two seat trainer has disturbed the peace and tranquillity of Orford. One part of me rises with excitement to try to see it but it has dipped down below the rooftops. It is like trying to find a mosquito at night in your bedroom with the lights off. Another part of me asks is it right that someone having a good time can create so much noise or am I just getting old and cynical? Was I concerned about the people over the Russian countryside when I was on a jolly flying one of the noisiest and most powerful jet fighter aircraft ever built? I do recall having some sense of guilt at the time but was too captivated by the thrill of the experience.

The eruption of the Icelandic volcano with the unpronounceable name (OK Eyjafjallajoekull if you insist) means that some of us may have to go without our Kenyan sugar snap peas for a few days and we all know of someone who is either marooned or unable to be with their families and friends. It may be that a little fissure in the Earth’s surface will change everything and make us realise that nothing it totally predictable, nor should it be.

I’m now looking out across to the present Orford Ness lighthouse that has arced its narrow white beam of light across the North Sea at night for nearly 200 years. Because of global warming and rising sea levels, sometime in the next three years, the lighthouse is likely to be washed away into the abyss. “Don’t worry” they say,” it was old technology that was about to be replaced by GPS anyway”.

Safe marine and air navigation has always depended on lights. Aircraft still reassuringly head towards the light of the Orfordness lighthouse whilst crossing the treacherous North Sea at night. Before the first lighthouse was erected on Orfordness, in one stormy night alone in 1637, 32 vessels were smashed aground onto Orford Ness.

Have we really become so clever and dependent on fossil fuels and addicted to computers and technology to ignore the rages of nature? Recent events have shown how unprepared we really are. What happens if we become too compliant on technology, flying and oil and everything? Can we be assured that business will continue as usual or will all the lights go out everywhere?